When I was attending Pensacola Christian College, one of the guest speakers that came in for the mandatory four-day-a-week chapel service castigated Christians for not respecting the Bible enough. He compared us to Muslims in order to illustrate how we were failing, explaining that Muslims handle the Qur’an with extreme care, propriety, and piousness. Depending on the interpretation, only those who are formally purified can touch the mus-haf (the printed Qur’an in the original Arabic), and it’s commonly taught that it should always be kept in a safe, clean place. The chapel speaker accused us of being negligent in our reverence for God’s Holy Word and said that most of us probably kept our Bibles on the floor in our classes, or right there on the glossy concrete in chapel.

He was right. Every day I stepped over Bibles that littered the floor on my way to my chapel seat. However, I felt so smug that day because I had been taught to properly respect the Bible. My Bible had never touched the floor. If I had to set it down somewhere– even on a desk– it was always on top of the stack. Even though I took notes in the margins, I was careful to keep them neat and clean. When the bonded leather inevitably started to deteriorate I twinged with guilt at not making sure it had lasted longer. I had been taught to see this book as holy.

And it wasn’t just the physical copy I revered, of course. The Bible was God-breathed, inspired, inerrant. I thought of it in terms that bordered on idol worship. It was how I ordered my life and all my decisions, it was sharper than any sword, it was the lens through which I viewed all information.

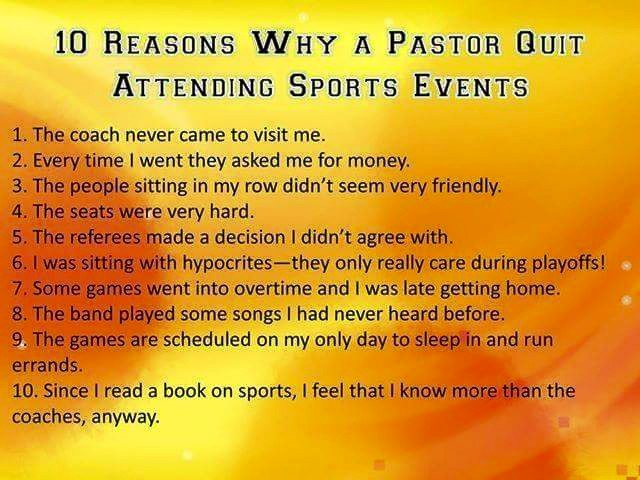

Over time, of course, my views have … shifted. You can trace that shift here, even. Toward the beginning of my journey here I said things like “[the Gospels] pass every single test for historical accuracy with flying colors,” which in retrospect is a trifle embarrassing at how naïve that sounds. Six months later I had reevaluated some things, and had arrived firmly at “I don’t know what it means for the Bible to be a divine book, for it to be inspired.” By early in the next year I was wrestling with my conceptualization of the Bible as “a magic book,” and in another six months I found myself barely treading water. In the middle of last year I was asking questions like “if Old Testament characters could be catastrophically wrong in their views, why can’t New Testament writers also be wrong?”

I feel like I’m stuck wandering around the Forest Temple in Ocarina of Time, and just when I get something untwisted I have to go back and twist it all up again, all while running around making sure a giant hand of despair and frustration doesn’t come whooshing out of the sky to smash me. Look at my bookshelf and you’ll see a theme– The Bible Tells Me So, The Sins of Scripture, Jesus Interrupted, Whose Bible Is It?, Misreading Scripture With Western Eyes, What the Bible Really Teaches … apparently I’ve had a years-long interest in trying to figure out what the hell the Bible actually is.

Turns out the fundamentalists were right. Once you give up their concept of inerrancy and really start examining the Bible, a lot of things fall apart on you. In a way I walked through the gate of hell and ignored the sign that read “abandon hope all ye who enter here.”

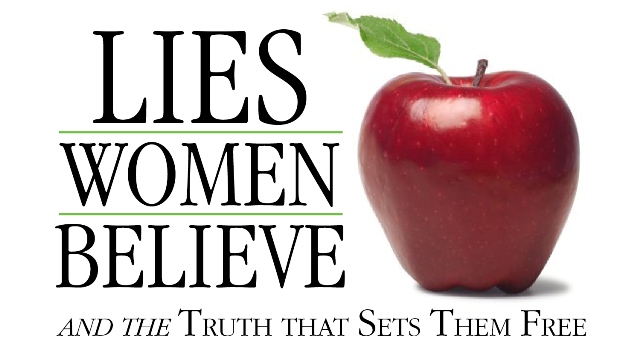

At this point I’ve given up on concepts like biblical inspiration or inerrancy, even broadly defined. I’ve been through the looking glass, and I can’t really go back. Once I opened the door to concepts like Paul was a man of his time and that means he was a misogynist and very wrong about some things, “biblical inspiration” became a frustrating idea to deal with. Because, at that point, even if Paul was “inspired,” it’s so loose a thing it’s ultimately unhelpful. I cannot believe that “I do not permit a woman to have authority over a man” could ever have been anything but sexist, and I especially abhor the idea that a misogynistic cultural reality from millennia ago should have any effect on how I’m “permitted” to use my abilities.

Paul and Peter and Matthew and Mark and Luke and John were human, and they were bound to get some things wrong. Maybe Paul actually was talking about “loving, committed, same-sex relationships” in Romans 1– it no longer follows for me that means that being gay and falling in love and getting married are sinful because of what some dead guy thought about buttsex.

I no longer accept the Bible as a moral authority. It endorses genocide at multiple points, has laws that treat menstruation as a sin, has prophets that revel in horrific violence and infanticide, views a rapist as “a man after God’s own heart,” includes misogynistic commands to church leadership, tells a man he was wrong for wanting to escape slavery, uses ethnic slurs … It’s filled to the brim with people doing and saying unpleasant things and getting patted on the back for it– either by the Bible itself, or by theologians for the last two thousand years.

A good story for this moment is when Abraham was told to sacrifice Isaac. I’ve discarded the evangelical narrative about it and embraced the Reformed Judaic perspective that Abraham failed his test. I’m allowed to listen to what appears to come from God and reject it, based on my conscience and my belief that God is love. Like Jacob, who became Israel, I get to wrestle with God, to demand things from them. Like Abraham– who learned better, fortunately– I get to argue with them about how I think what they’ve just said is wrong. Like the Syro-Phoenician woman, I fully expect to win a debate with Jesus.

All of this doesn’t mean that I see the Bible as worthless– as the above should show, far from it. I love the Bible now more than I ever have. I love that I can be confused by it, enraged at it, and challenged by it. I love that I am a member of the same faith that brought doubters, thinkers, tricksters, liars, poets, and lovers together to create a sacred text filled with problems and contradictions and arguments it has with itself. James essentially spent an entire letter sub-tweeting Paul: “not going to name names, guys, but faith without works is dead *coughPaulcough*.”

I don’t have to waste time justifying why God commanded genocide– because I’m convinced they didn’t. I don’t have to come up with convoluted reasons for why imprecatory prayers are ethical. I’m perfectly free to ignore that Paul told a man to return to a life of slavery.

I can look at the Bible and, when necessary, say fuck that nonsense.

It’s opened up a whole new world for me. I get to rediscover everything. Did Jesus mean “you should spend all your time witnessing” when he asked the Apostles to be “fishers of men,” or by making a literary reference was he calling them to the task of restoring justice and mercy to Israel? If the Holy Spirit– who is always referred to in the feminine– was the one who visited Mary when she became pregnant, doesn’t that make God just a teensy bit gay? I can read Ruth’s speech to Naomi– the one we use in marriage ceremonies today– and think “yup. That woman is bi.”

The Bible is mine now. I can fully own what it is, and what it means to me. I can turn it upside down and inside out, create headcanons about it, and make perhaps wild, conjecturous, far-flung connections that strain credulity if I want to. I’m finally throwing off the heavy yoke of the evangelical view of the Bible, and embracing the notion that when Jesus said “you have heard it said, but I tell you that was wrong,” he was talking about the Bible.