To long-time readers, something you might have noticed is that my views of the Bible have shifted quite a bit from when I first started writing this blog. I’d moved away from the inerrantist position by spring 2013, but if I knew then what my thoughts would be now five years later, 2013 me would probably be horrified. I no longer think the Bible is infallible or inerrant, and I only think it’s “inspired” in the mundane, artist-having-a-stroke-of-genius sense of the word. I think the Bible is written by humans and it can be wrong.

It’s still the framework for my belief system; I appreciate that even if it can be wrong, it’s still full of wisdom, human experiences, and rich stories — whatever else the Bible is, it is the preserved history of how many Jewish and Christian believers have tried to understand and relate to the divine. Even stripped of perfection and divinity, the Bible is still powerful, and still incredibly precious to me.

Most of the discussions around an “open canon” revolve around what would happen if we discovered and authenticated other books or letters written by the biblical authors. What if we found a letter the apostle Paul wrote to the churches at Smyrna or Berea? What if we found texts penned by the apostle Junia?

While those are fascinating questions, I’ve been mulling over what the biblical canon means to me in recent weeks, and I realized that what makes the Bible important to me includes the possibility that other books, contemporary books, could be included into a future biblical canon. I think of the biblical canon in much the same way that I view literary canon(s) more generally: works are included in a literary canon because of their cultural significance, elevated writing, quality of art and thought, and their ability to provoke a lasting response emotionally and/or philosophically.

So looking around at the books we have today that fit this definition but also include a theological component, what sorts of works do I think fit into a modern biblical canon? If we had another Council of Nicea today and were deciding what to include, what would I advocate for? It’s been an interesting thought experiment and I thought I’d share my results so far with y’all.

***

I’m familiar with the Shepherd of Hermas because I was utterly obsessed post-college with the formation of our current biblical canon. For a long time and in several churches, Shepherd of Hermas was included in their canon, but it didn’t quite meet the criteria of the Nicea folks so eventually it was thrown out. I would add it back in because of its cultural significance to early Christians– it shaped a lot of theological conversations in the early church and was widely read by many of our church fathers and mothers. It also has some interesting things to say about Jesus’ divinity (why it was probably not included) and the systemic nature of sin. I like it because (in my opinion) it assumes that the study and ethics and theology are, practically speaking, the same pursuit.

Written by Julian of Norwhich, Revelations of Divine Love is an absolutely essential book for modern Christians. It’s the first book written in English by a woman that we currently know of, and was rediscovered by modern Christians around the turn of the twentieth century due to her work being republished in a near-complete, accessible form. We know her writing was preserved in various places throughout England and Europe so it must have had a least some measure of popularity to have spread as far as it did, but she’s far more widely known now than she was during her lifetime. I think including Revelations of Divine Love would be an enormous boost to the canon because her theology is rooted in compassion and love. She sees God’s love as motherly, and God’s nature as primarily benevolent. Our Christian canon could certainly benefit from a lot more of that.

Camino de Perfección or El Castillo Interior (Way of Perfection or The Interior Castle)

… or perhaps both. These two are written by Teresa of Ávila, and are guides for Christian living and practice from the perspective of a Christian mystic. The Interior Castle was so well-written, well-constructed, and well-argued that Descartes ripped it off for many of his own ideas. Way of Perfection spends its time explaining how to practice contemplative prayer in order to achieve divine ecstasy, and The Interior Castle expands on that to Christian living more generally. The Interior Castle argues that the ultimate goal for any Christian is active, embodied work in helping others and making the world a better place. Shouldn’t be a surprise that I have a soft spot for Teresa (also some of her writing is … well, it would scandalize a lot of modern Christians. What’s not to like about that?)

The beauty and power of Walter Brueggemann’s The Prophetic Imagination is summed up for me in his dedication: “For sisters in ministry who teach me daily about the power of grief and the gift of amazement.” Brueggemann is defining what he thinks a prophet should be, and what a prophet should do. He draws heavily on Moses and Jeremiah’s resistance to oppressive power structures, and looks ultimately to Jesus for our example in siding with the marginalized, vulnerable, and oppressed. I’m not sure there’s a modern work more broadly impactful than The Prophetic Imagination–in my opinion, many (most?) modern Christian conversations about how Jesus cared for the oppressed stem from this book.

The Cross and the Lynching Tree

I include this in the list because if there’s a book I think every single white Christian in the US needs to read, it’s The Cross and the Lynching Tree. Part of most definitions of canon is an element of “books everyone should read in order to be considered well-read,” and I’m convinced that my proposed biblical canon would have a gaping hole in it without Cone’s book. In it, he argues that the Cross gives African-American Christians the power to “discover life in death and hope in tragedy,” and challenges white Christians to confront our passive complicity. It’s a deeply powerful work.

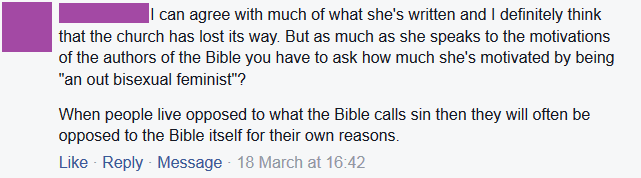

The most common term applied to Elizabeth Schüssler Fiorenza’s In Memory of Her is “groundbreaking,” and it is one of the foundational texts of not just Christian feminism but also how we understand the origins of the Christian church. Fiorenza is an incredible scholar and how she shines a light on how women participated in building the Church is enough to recommend In Memory of Her for my canon, but she created something more than just an academic text on Church history. She also challenges us to see beyond the patriarchal boundaries of the texts and toward a creative world that isn’t circumscribed by the limits imposed on us by centuries of male domination.

To be honest, I would wipe out the psuedepigraphic pauline epistles and replace them with Brené Brown’s Daring Greatly in a heartbeat. Brown is first and foremost a researcher, and her background and the intense work she’s done around vulnerability, shame, wholeheartedness, and empathy is the foundation for Daring Greatly, and is what makes the book so incredibly powerful. Most of the people I know who’ve read it have needed to take it in stages because of how provocative it is– it’s an eye-opener, and emotionally difficult. It’s also one of the most transformative and helpful books I’ve ever read. I consider Daring Greatly to be a modern work of public theology, even though she doesn’t use religious language in the book. I think the problems she’s discussing and their solutions are fundamentally spiritual and theological– and Daring Greatly is proof that we don’t need religion to talk about them.

I joke around sometimes with Handsome that Fred Rogers was the Second Coming of Christ and all of us missed it– and to be honest, I’m like 1% serious about that. An Atlantic review of Won’t You Be My Neighbor, a biopic about Rogers, calls the children’s TV program “quietly radical” and that captures a lot of my feelings about Mister Rogers Neighborhood. The kindness, compassion, love, grace, bravery, and patience that Rogers exemplified and that he teaches us to replicate in our own life is life-affirming and life-giving. If we all paid attention to Rogers and applied his lessons and example to our own life, the world would be a much better place. He’s one of the reasons why I’m still happy to call myself a Christian: to me, Rogers is a modern day example of what Christianity looks like.

***

I’m curious about what all you would add, if you could. There were a lot of books I had to leave out for time’s sake– works by Du Bois, Pelagius, basically anything from the Protestant Reformation/Counter Reformation, poetry, letters, novels because there is just so much— so what would you bring with you to The Council of Nicea 2018 CE?