Tamara Rice is an editor and write and a frequently loud-mouthed advocate for victims of abuse within the church who blogs at Hopefully Known. “Learning the Words” is a series on the words many of us didn’t have in fundamentalism or overly conservative evangelicalism– and how we got them back. If you would like to be a part of this series, you can find my contact information at the top.

trigger warning for child abuse, sexual abuse, and spiritual abuse

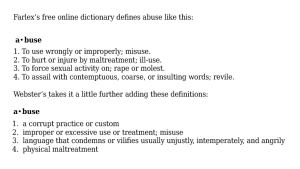

Where I come from abuse was a term reserved for vicious violence. I’m not really sure why or how this protection around the word came to be, but I know that great care was taken to distinguish between parents who were abusive and parents who were merely … very bad parents. Between sexual boundaries being crossed in a way that was sexually abusive and in a way that was more … molestation. Between spiritual authority being misused in an evil way that was spiritually abusive and in a way that was simply … unfortunate. Abuse, in short, was reserved for what I now might put in the category of sadistic torment—the stuff they make horror films about.

Under these narrow definitions, abuse was rarely encountered in my growing up years (or so we thought), and maybe that was the whole point. Defined as such, abuse was kept at arm’s length, out of our circles. Abuse happened to people on the news and in salacious Stephen King novels, it didn’t happen to us, it didn’t happen in our fundamentalist Baptist church, it didn’t happen in the missionary community we were part of overseas.

~~~~~~~~~~

By the time I reached my 30s I had very little to do with the faith community of my childhood. I had married a man in ministry and had gone on to be part of churches and religious organizations where legalism was rare and the kind of fundamentalism I’d grown up with was rarer still. I got it out of my system and left it behind. And then in 2011, I got sucked back in.

I began to fight alongside several old friends to bring justice for the victims of a missionary from our childhood and to call into account the Baptist mission board who had been mishandling the pedophile’s exposure for over twenty years.

Even now, it’s hard to put this story into a few brief words. The pain is still thick at the back of my throat and the journey isn’t over. But from the moment I stepped back into that fundamentalist world, the term abuse grew to encompass so much more than violence. I grew to understand it in its fullness, as it was meant to be understood–as I wish I had understood it from a very young age.

The justice endeavor began as an effort to bring healing to a friend and her family who had been deeply wounded by the pedophile and mission board, but over time it became very clear that I suffered sexual abuse myself—something I had long pushed back and denied and reasoned away, despite it explaining decades of emotional instability. New information made it undeniable, and I had to face the things my mind had hidden. Then, as I fought for justice, I became the victim of spiritual and emotional abuse as well.

First came the e-mails and blog comments from total strangers calling me a tool of Satan and an enemy of the gospel. Verses were thrown at me—at us—and we, the victims,were admonished not to touch “God’s anointed.” The vile things that self-proclaimed Christians will say in anonymity is appalling. If self-righteous curses of “shame on you, you whore of Satan” could kill, I’d be dead from the anonymous e-mails of vitriol and hate I have read.

The harder we pushed for justice, the closer the abusers came. Now it wasn’t just strangers dishing out spiritual and emotional abuse on the internet, it was people we had called “aunts” and “uncles” in our youth. Verses, again, were thrown at us. We were reminded to forgive, reminded of the supposedly innocent family members who were embarrassed and hurt by the pedophile’s public exposure, but who—let’s face it—probably knew a certain amount but lived in denial all along. “What about them?” the emails would say. “You’re being evil and cruel. They don’t deserve this.” And they, the family, didn’t deserve it. That’s true. But neither did we, and neither did any other child.

False familial titles (the cult-like “aunt”/“uncle” monikers) and childhood nicknames were doled out in long e-mails, phone calls and voicemail messages from those whose were rightly being questioned. I stopped taking the calls, stopped listening to the messages, but not before a few left their mark. “This is your ‘Aunt’ ______. We’re hurting so much over all these accusations. We looove you, Tammy,” she said, her voice thick with emotion I couldn’t understand given we’d hardly known each other, hadn’t seen each other since I was fifteen, and she was using a name no one outside my family had called me in over two decades.

It was a poorly disguised attempt to guilt me into silence over a leadership “mistake” her husband had made. Her husband should have be shouting from the rooftops that he’d been wrong, done something criminal under the mandated reporting laws, done something morally shameful. But instead the wife was sent to sway me, to spare her and their grown children this sadness.

Her voicemail haunted me for weeks, not because she got to me, because she didn’t. It was because she had tried. Because she had invoked love and false familiarity and spiritual obligation in her desperation to silence me. I was shocked—utterly shocked—at the subtle insidiousness of it.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

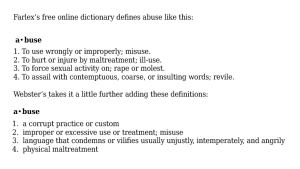

The misplaced resentment against us, against me, personally, grew to epic proportions when a friend exposed a second pedophile a few years later—and by misplaced resentment I mean more spiritual and emotional abuse. I mean using scripture wrongly and improperly, using relationships and pasts and church authority wrongly and improperly, I mean hurting and injuring by maltreatment, I mean the continuation of corrupt practices and customs, I mean language that condemns and vilifies unjustly and intemperately. I mean all of those things above that Webster’s and Farlex tell us are the definition of abuse. I suffered these things publicly and privately from the mission board, from people I barely knew, and from people I knew well.

At one point, a man who grew up on the same mission field as I did launched a Facebook page vilifying me. His page banner labeled me a fascist, but the reality was he didn’t even know me well enough to use my married name of almost twenty years. One by one, I watched as adults and former friends of my formative years overseas “liked” his page, all because they didn’t like men they admired being exposed for the havoc they had wreaked in the lives of young women who were now middle-aged and grown and no longer being silent.

It wouldn’t have been so bad, really, except that then this Facebook group started in on my faith, mocking me, using my words against me, twisting who I was. Knowing I shouldn’t read their bitter words that came from a narrow view of faith I didn’t even subscribe to, I read anyway, sickened that I had become the target of hate and abuse when there were pedophiles sleeping as free men.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The spiritual and emotional abuse of these years, and the time I spent coming to terms with my sexual abuse—it’s all left me battered.

I retreated for quite a while after the Facebook incident, and I’ve never made a full comeback to that particular justice effort. I wish so much that I could tell you that justice and truth won out. That doing the right thing and exposing sin (no, make that crimes) paid off. But it didn’t and it hasn’t. It has been the most painful exercise in futility of my life.

My consolation, however, is this: I know what abuse is now. Sexual. Spiritual. Emotional. And because I’ve learned the word I can call it what it is. I can give it a name. I can see it when it happens to me or in front of me. And I can cry and grieve and hurt, but then I can get up and walk away and find healing in a safer place. Because the word has lost its power now that my vocabulary has grown.