[trigger warning for child sexual abuse, rape, domestic violence]

I’m not entirely sure when it happened, but from the reading I’ve been doing, sometime in the last 30 or so years there’s been a subtle shift in how churches talk about growth. What my reading tells me is that this is at least somewhat connected to the rise of the “mega church,” with it becoming impossible for pastoral staffs to simply look around their churches and understand who their congregation is.

There’s a certain appeal to evaluating church growth by the numbers, especially when church sizes seem to be ballooning. Applying business models that are intended to bring growth can be extremely useful for a variety of organizations, and churches are, really, just organizations. Organizations that are almost totally defined by “growth,” for better or for worse. Even in Acts, as my partner pointed out yesterday, the apostles tossed around a lot of numbers. Peter, especially, has one famous speech about Pentecost and how many were saved.

In the churches I’ve been in that have talked numbers– “X many people were saved! X many people were baptized! X many people have joined our church in the last year!”– the focus has almost always been hope. Numbers are real, concrete indications that we’re headed in the right direction, that what we’re doing is making a difference. Numbers are people.

But, in the last year, my perspective has changed quite a bit. I used to hear those numbers shouted from pulpits all over the country and exult right along with the preacher. And, in some ways, I still do. But, when I hear about how many people regularly come to church, and how many children are in Sunday school, and how many babies are dedicated, a completely different set of numbers starts spinning around my head, and it makes my heart ache.

My heart has been especially broken this week, since Bob Jones University decided to terminate the investigation they’d hired GRACE to do. I wasn’t a student of BJU, but I did grow up in that world and I know many people who were– and I know how important the GRACE investigation was to them, how much hope it had given them that maybe, just maybe, BJU could turn over a new leaf.

But, just like the Association of Baptists for World Evangelism, and just like Sovereign Grace Ministries, and IBLP, and just like countless other churches and ministries all over the globe, BJU has decided to do what far too many other Christians have done: turn a blind eye to the abuses happening under their watch– abuses they are allowing to happen through their silence, abuses they are complicit in.

I know how hard it is to face the bleak reality that there are so many people willing to hurt others. That abuse in so many forms is commonplace. I can’t even begin to imagine what it would be like to be a pastor and stand in front of your congregation and know that there are abusers and victims in your church. That you could be shaking the hand of a pedophile or rapist after church. That you could be eating dinner in the home of a batterer. That you can’t know. Not for sure.

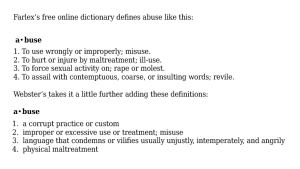

But, this is a reality that does need to be faced. We need to look it dead, square in the eye and let it change us. We need to keep in front of us, always, that people are hurting and desperate and don’t know a way out. That most victims don’t even know they’re being abused, that abusers cloak themselves in forgiveness and grace and redemption, that some abusive husbands will use “I am the head of this home and you are my wife, so you must submit to me” as a weapon.

So, because this needs to be something that we know, something that changes how we talk, changes the advice we give, changes the way we love the people in our churches– I’ve broken down an average church size by the most reliable statistics we have.

Most churches in the United States have an average church attendance of around 500 adults, 125 children. Most congregations are dominated by married adults, so in this “average church,” there are 200 married couples, 275 women and 225 men, 64 girls and 61 boys. This means that in this church:

- At least 40 marriages are abusive. Studies show that anywhere from 20%-35% of all intimate relationships are abusive, and many are physically violent. Physical abuse is not the only form abuse can take, and other types of abuse are just as damaging.

- As many as 20 women are being consistently raped by their husbands. Studies performed by Susan Estrech and Diana Russel indicate that 10% of married women describe most of their sexual encounters with their husbands as non-consensual.

- 38 of the men were sexually abused as children.

- 68 of the women were sexually abused as children.

- Another 55 women have been raped, probably in college.

- 7 men have been raped as adults, although if you are near a military base that number is probably higher.

- 16 of the girls will experience sexual abuse.

- 10 of the boys will experience sexual abuse.

- 1 or 2 of these children are being physically abused by their parents.

- It is possible that there are 9 child sexual abuse perpetrators in this church, since 30% of all child sexual abuse perpetrators are close family relatives– usually male relatives, although in 9%-14% of cases the pedophile is a woman. Another 30% of the time the perpetrator is another, older, minor.

That’s a possible 256 people– 40% of this “average” congregation— who have been violently wounded by some kind of horrific abuse. This isn’t something we can afford to ignore. This is something that should utterly break us and radically transform everything we do as a church body. We can’t be dismissive of hurt. We can’t ignore that there’s darkness and pain and suffering. We can’t preach messages filled to the brim with ideas that can be turned into weapons by abusers. We can’t afford the blithe, non-committal “if you’re being abused, you need to get out,” and then move past that as if it doesn’t happen here. We have to stop burying our heads in the sand with our “God doesn’t give us more than we can handle!” and our “faith like a mustard seed!”

We have to be the ones who love the hurting and the broken, who acknowledge their pain.