[content note for bigotry and homophobia]

If you’re anything like me, this is a conversation you’ve probably had with your parents:

“Ugh! I just hate her! She’s so awful!”

“Samantha, don’t say ‘hate.’ Hate is a strong word.”

“Fine, then, I strongly dislike her.”

I always felt like I was being particularly witty, since “intense or passionate dislike” is the dictionary definition of hate. Colloquially, hate does have a connotation that “intense dislike” just doesn’t encompass, but Christian culture has bent and twisted the word hate until it’s practically meaningless. When a Christian looks me in the eye and says “of course I don’t hate you!” what they actually mean is something akin to I don’t personally want to assault you with my bare hands. To a conservative Christian, unless they’re actively and personally wishing you —personally– harm, than you can’t possibly accuse them of hating you.

That’s how Thabiti Anyabwile and the people who agree with him can say this:

Return the discussion to sexual behavior in all its yuckiest gag-inducing truth … In all the politeness, we’ve actually stopped talking about the things that lie at the heart of the issue–sexual promiscuity of an abominable sort … I think we should describe sin (and righteousness) the way God does. And I think it would be a good thing if more people were gagging on the reality of the sexual behavior that is now becoming public law, protected, and even promoted in public schools …

That sense of moral outrage you’re now likely feeling–either at the descriptions above or at me for writing them–that gut-wrenching, jaw-clenching, hand-over-your-mouth, “I feel dirty” moral outrage is the gag reflex.

… and then infuriatingly believe that their explicit perpetuation of an active and intense dislike isn’t an act of hatred. They can do it because they’ve intentionally forgotten that hatred is “intense dislike” with just slightly more oomph– the oomph of thinking “I feel dirty” or “those people are so sick!” They can do it because they’ve lost their sense of communal responsibility. To your average evangelical Christian, sin is personal and it is individually committed. They are blind to systems, to institutionalized hatred. They blatantly refuse to acknowledge how every single one of their homophobic actions and beliefs feed into a system of hate.

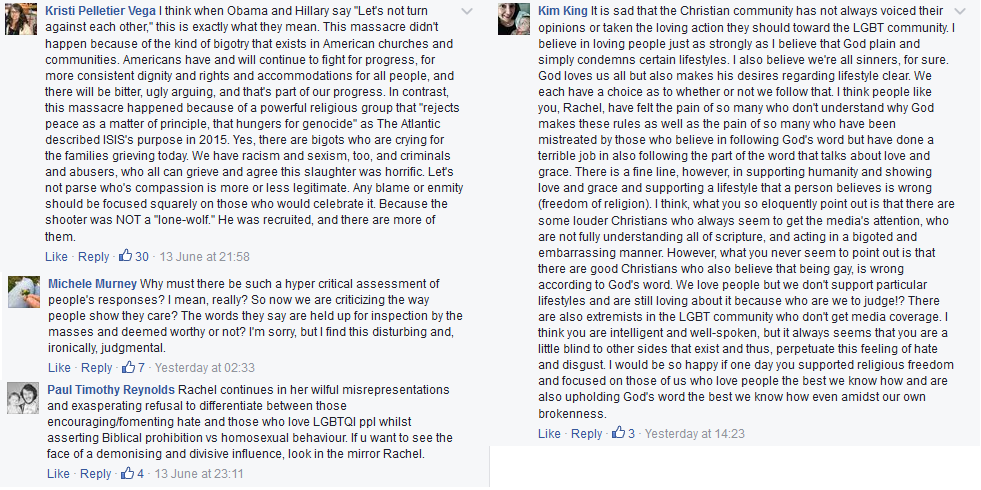

It leads to these, which are just a handful of the awful comments on Rachel Held Evans’ post where she reminded us that “there was a body count before Sunday”:

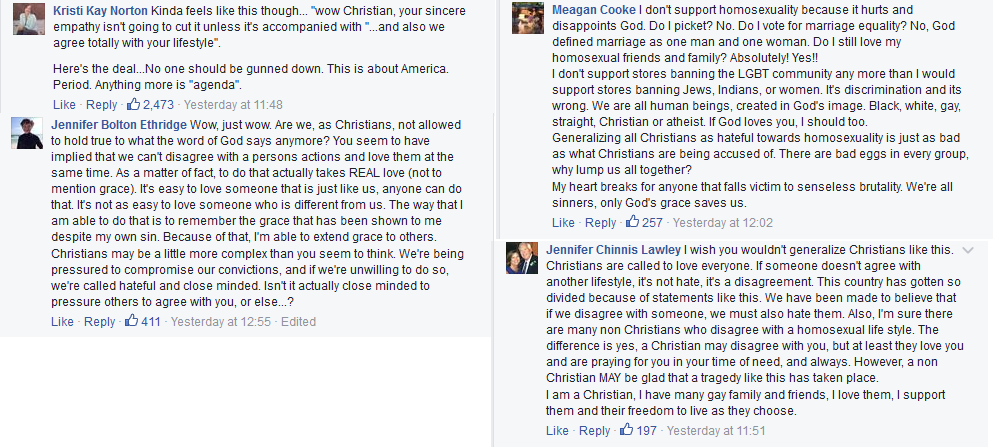

Or these, from Jen Hatmaker’s post where she said “We cannot with any integrity honor in death those we failed to honor in life”:

“It’s not hate, it’s a disagreement.”

They say it over and over again and are just so utterly baffled when I choke on rage, frustration, and despair. They’re just so very confused when they look at me and say “I disagree with your very existence because of my pet biblical interpretation, but that clearly can’t be hate. If I hated you, I’d want to punch you or something. Since I don’t want to punch you in the face, that must mean what I’m saying is loving!” and all I want to do is rip my skin off and gnash my teeth at them.

Believing that I don’t have the right to exist exactly as I am is hatred. Fighting against my civil rights is hatred. Believing that Romans 1 applies to me and that I’m therefore “worthy of death” is hatred. Referring to my existence as an abomination— which has happened to me multiple times over the last few days– is hatred. One man on my public facebook page told me I was abomination, that my existence was just as evil the eyes of God as mass murder, but then two comments later said that he “loved” me and “mourned the deaths in Orlando”!

Not only have they twisted the definition of hatred into something so deformed it’s beyond recognition, they’ve done the same thing to love. Here’s the thing, though: when Jesus said they shall know you by your love, it comes with the pretty basic assumption that your “love” should be recognizable to people who don’t share all your pet theories. If people who don’t share your interpretation or your faith look at your actions and say “that looks an awful lot like hate to me,” your response shouldn’t be “oh, it only looks that way to you because you’re not a conservative evangelical like me!” It doesn’t make any sense.

On top of that, Jesus also said this:

You have heard that it was said to the people long ago, ‘You shall not murder, and anyone who murders will be subject to judgment.’ But I tell you that anyone who is angry with a brother or sister will be subject to judgment. Again, anyone who says to a brother or sister, ‘Raca,’ is answerable to the court. And anyone who says, ‘You fool!’ will be in danger of the fire of hell.

Raca literally means “to spit.” It’s a reaction of disgust, of revulsion– in the words of Thabiti, it’s the “gag reflex” at work. And Jesus compares that reaction to murder. John, later, makes the connection explicit for anyone who might not have gotten it:

Anyone who hates a brother or sister is a murderer.

I’ve seen hundreds of Christians over the last four days protesting against the connection that my LGBT community has been making: this is on you. You’re responsible for creating him and the homophobic culture he breathed in every single day of his twenty-nine years. You weren’t the gunman, but you’re the culture that built him. You’re the bullets in his gun.

To be honest, I never really, viscerally, understood Jesus’ indictment of hatred until Sunday. I understood the larger point of the sermon on the mount, that sin isn’t a matter of rules and regulations but begins in the hearts and minds of men. I understood that he was reorienting a culture away from their preoccupation with the Law and focusing them on their beliefs and perhaps deeply-buried motives. But saying that anger and disgust and revulsion were on par with murder seemed so extreme–surely this is one of those times Jesus was speaking hyperbolically?

I don’t think he was. I think he was talking about systems. He was talking about the creation of a system where Robert Dear could walk into a Planned Parenthood clinic and open fire while shouting “no more baby parts!” and then declare “I’m a warrior for the babies!” The hatred that stirred the “Center for Medical Progress” into slander prompted Robert to commit murder. Just a little bit ago James Dobson practically begged for someone to shoot LGBT people, trans people in particular, with a desperate plea of “Where is today’s manhood? God help us!” Thirteen days later someone in Florida decided that he was enough of a man to actually pick up the gun and go do something about those abominations.

You have hated us for years. You have been killing us for years. Now, it’s time for you reconcile yourselves to us, to seek diallasso— a change of mind, a change of heart.