So, I got an interesting question on twitter this morning. “John” asked me “how does modern day feminism and Christianity complement each other?” and it occurred to me that while I’ve talked a lot about how I became a feminist, and why I’m a feminist, and why I think Christianity desperately needs feminism . . . I don’t think I’ve talked about why I specifically identify as an egalitarian and Christian feminist, even though I’ve spent quite a bit of time talking about why I disagree with complementarianism.

Even if I left Christianity and abandoned my faith entirely I would still be a feminist– in fact, if I do eventually leave my faith it will probably be because I am a feminist. To me, feminism isn’t about making sure that men and women are indistinguishable (and I would posit that feminism has never argued for that, even though it was painted as doing so): feminism is entirely about fighting for the marginalized, for the oppressed, for the abused, for the silenced. Flavia Dzodan said it better than I ever could: my feminism will be intersectional or it will be bullshit. Intersectional, meaning that as a feminist I will fight for equality for all people– for LGBTQ people, for people of color, for men damaged by the messages of patriarchy and domination. If I abandon Christianity, it will be because I’ve concluded that there is no hope for equality based on a thorough and deep investigation of Scripture.

However, even though I have deep struggles with the Bible and what almost feel like unanswerable questions about infanticide, genocide, rape, and the slaughter of innocents, when I read about Jesus, when I read the Gospels and then the following letters that circulated in the early church, I see hope for the oppressed. When I sang “O Holy Night” during my in-laws Candlelight Service, the words “Chains shall he break, for the slave is our brother– and in his name all oppression shall cease” shook me to my core, and I had to stop singing so that I could weep.

All oppression shall cease.

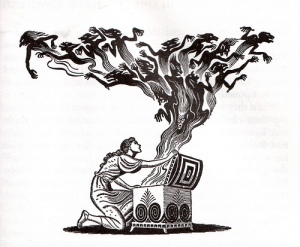

Christian feminism and its sister egalitarianism is about fighting against the oppression of women in the Church. We have inherited a long history of open misogyny practiced by many (if not most) of our Church fathers. Martin Luther called marriage a “necessary evil” and said that it’s better for women to bear as many children as possible and die in childbirth than it is for a woman to live a long life. Tertullian described us as “the gateway to hell.” Even biblical writers blame Eve’s weakness almost entirely for the Fall, taking the same approach that Adam did when God questioned him.

We seek to honestly struggle with these passages, to understand them in light of what we see as Jesus’ message. When I read the Gospels, what I see is a story about how Jesus lifted up the oppressed, how he exalted second-class citizens to equality. I see Jesus being born of a woman and Mary exclaiming:

He has done mighty deeds with His arm;

He has scattered those who were proud in the thoughts of their heart.

He has brought down rulers from their thrones,

And has exalted those who were humble.

He has filled the hungry with good things;

And sent away the rich empty-handed.

I watch as his parents take him to the Temple, and it is a woman, Anna, who recognizes Jesus as the Messiah and who speaks of him to all those “searching for redemption in Jerusalem.” I follow him through his ministry, when he speaks to uneducated women the exact same way he speaks to Pharisees and biblical scholars. I delight when he declares a woman has bested him when she says “even dogs eat crumbs from the master’s table.” I rejoice when he recognizes the full rights of women when he calls one of us a “Daughter of Abraham.” I glow with the pride Mary must have when he says that she’s chosen her rightful place to learn at his feet. I cry when it is only women who remain, following him to the tomb– and then dance when the Resurrection is announced by a woman, who is revered as “The Apostle to the Apostles.”

And it doesn’t end there– the stories keep pouring in. Prisca, who teaches Apollos a better way. Junia, an outstanding apostle. Phoebe, the deacon from Cenchrea. Philip’s daughters, who prophesy. Mary, Trephena, Truphose, Persis, Eudoia, Synteche, Damaris, Nympha, Apphia … and many others who go unnamed but labor side-by-side with the Twelve in spreading the Gospel.

I see all of these stories, and then I see a few scant passages with murky histories and difficulties in their interpretations, and I can’t accept that a few words we don’t clearly understand can completely undo the honor and praise heaped upon women– women who Paul says had been a “leader of many and of myself as well” (Rom. 16:2).

I understand why this is an ongoing conversation in the evangelical community in America. There is a tension here, between these ideas. There is a reason why many intelligent, perceptive people are complementarians. I disagree with them– sometimes, I disagree with them violently— but I get it.

However, I believe that all oppressions shall cease, and patriarchy– even patriarchy christened by earnest Bible-believing men and women as “complementarianism”– is oppression. I believe that this is one of the core ideas in the Gospel– that everyone, every person no matter their gender, sex, color, or status is equal. That under the Gospel, there is no bond or free or man or woman or Greek or Gentile. We are all one in Christ, the heirs and children of God.

To me, there is basically no difference between my feminism and my faith. The two are so integrally connected; all my reasons and feelings are tied up together. I am a Christian because I am a feminist– I believe that Christianity’s core message is one of freedom and hope. I am a feminist because I am a Christian– I fight for equality because I believe it is both the only moral, right, just thing to do and because I seek to follow where Jesus led.