The first Holy Week I was blogging, back in 2013, I wrote a brief post for Good Friday, describing the resonance I felt with those who watched Christ suffer, bleed, and eventually die from being crucified as a rebel:

A few years ago, I stood in a dark place. The ground trembled and shook under me, and I stared up at heaven and watched my god die. Everything that I thought I had known– known with an absolute, unreachable certainty, was gone. Shattered. In a moment, in the space of a few words, it felt like everything in my universe was a lie. I had been deceived, tricked.

Horror-struck, I watched the truth pierce the side of the person I’d thought was god made flesh, and the pain was so intense I could feel a hollowness inside– an emptiness torn apart by swords and spears. Truth and reason and experience and emotion were the pallbearers that carried my faith away. And suddenly, the world was cold and dark and empty, because all the light had gone out. The veil was torn, and I couldn’t see anything worth hoping in behind the curtain. It was just a room. It was just a piece of lumber, a few pieces of iron. It was just an empty space carved into rock.

Tears washed my face in the night; my heart echoed along with the cries of “why can’t you save yourself? Why can’t you save me?” Why did I carry a back-breaking cross in your name?

They carried him away and buried him under a mountain of shame and terror. I sealed the door shut with guilt and fear and betrayal and anger and rage.

Eventually, the sun shone, piercing clouds and making the world seem strangely normal again. I went back to work. I continued learning. I talked with friends who never knew what I had just witnessed. I hid in upper rooms I created inside of my head, places where my god had never been– and never would be. All the promises I’d ever known were broken, and the lie of them was bitter. I couldn’t speak them to another person, and every time I offered an assurance to another, it felt like feeding them false hope and platitudes. I wanted to rage inside of my own temple and hear the crash of silver on marble tile.

He was dead. The god of my childhood was nothing more than a corpse.

I wrote all of that, and then immediately wrote the post that followed it, words filled with hope and ultimately confidence. It’s been a long three years since then, though, and my faith has continued to take heavy battering. It’s shifted, struggled, grown, transformed. In many ways, the sort of Christian I was three years ago and the Christian I’m becoming bear little resemblance to each other. Back then I still thought it was important to cling to a certain set of facts to be a Christian, and now I feel that facts have very little to do with faith at all.

I’ve had my faith challenged, shaken, even broken at times. In a way, I’ve faced down the same choice Judas did: abandon Jesus because what he offers makes no earth-bound sense, or go to Good Friday with him like Mary Magdalene? Some days, like Judas, I almost feel like giving up. If I can’t know that Jesus is resurrected, if I can’t be sure that he’ll come back to break all chains and cease all oppressions, then what is the point? If Christianity doesn’t make any logical, realistic sense, then I might as well side with those who are more pragmatic– dreams and belief and pixie dust don’t do anything real.

For me, it feels like Good Friday isn’t just a day during Holy Week– it’s every day of my life.

Nearly every day I stare at a bloodied cross and a body laid to rest in a tomb, and I wonder and doubt. I wonder sometimes if I’m being completely ridiculous. If there is a god, then why does the world look like this? Nearly every day I lay my God to rest again. I bury him. I mourn him.

But, I still have a choice in those moments. Maybe my God is dead. Maybe he’s not miraculously coming back from beyond the veil to give me the proof he gave Thomas. But does it matter? If I want to follow him, does whether or not he resurrected and ascended truly make the difference between whether or not I try to do what he said? If the resurrection never comes, if I’m never given concrete-hard proof that Christianity is the religion, what happens?

Do I stop believing that it is my responsibility to make the world a better place? Do I stop trying to bring an end to misogyny, racism, ableism, transphobia– bigotry in all its forms? Do I stop seeing every person as worthy of love, respect, kindness, equality, and justice? Do I lose hope in redemption for each of us individually and for the world?

If my life is a perpetual series of Good Fridays, do I spend all my days hiding, afraid of leaving an upper room of privilege and security? Do I spend these hours more afraid for myself then for those Jesus charged me to clothe and feed and heal? Do I huddle together with other Christians, separate and unmoving, cut off from our communities, unwilling to reach out and love the widow, the orphan, the prisoner?

We’re all moving through Good Friday, really. Maybe you have the assurance that in three day’s time Jesus will roll back the stone and walk among us in the flesh. Maybe, like most, you’re utterly convinced that the resurrection is a well-established fact, testified by multiple eye-witness accounts and all the other evidence Habermas and Strobel and Licona and Wright have spent books and books explaining.

Except, in the end, even with all of the arguments, all the proof in the world, we’re all still facing the same choice: hide in our upper room, or go out and do what Jesus showed us. We could be so afraid of the world around us with all its dangers and threats and, like Judas, turn to political powers for our protection. Or, we could leave the false security of the upper room and take up the same cross that Jesus bore.

That’s the choice of Good Friday. It’s a choice between fear and love.

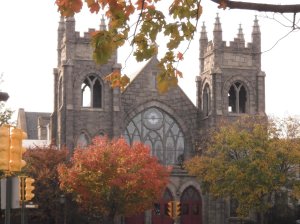

Photo by Der Robert