trigger warning for transphobia

I love gender swapping.

LOVE IT.

And, I’ve also been fascinated by it for as long as I can remember. I started writing gender-flipped fanfiction stories of Star Wars and Lord of the Rings when I was 11, although I had no idea that’s what I was doing at the time. Part of it was realizing that the books and stories that I adored had no women in them, so I provided my own by making Obi-Wan or Legolas a girl. But, as I wrote out those rather silly little stories in leftover scraps of notebooks, I was doing something interesting: when I transformed Obi-Wan into a girl, what I identified about his personality and character stayed the same. I wasn’t seeing Obi-Wan or Legolas as men, and I wasn’t internally labeling their characteristics as inherently masculine. The fact that I wasn’t amputating their character or personality when I made them women speaks volumes for my frame of mind when I was younger.

As I got older, though, I stopped doing that. I was still writing fan-fiction, but I started creating my own female characters and inserting them into the larger narrative– although these characters were literally silenced or repressed in some way. One character had her memory wiped. Another was brainwashed into believing she was weak. All of these stories revolved around these women discovering themselves and their power (oh, and falling in love with either Obi-Wan or Legolas . . . blush).

I forgot about gender-swapping or gender-flipping. My innocent childhood belief that men and women are people with their own individual differences was slowly eroded over years of gender-essentialist conditioning. Lines appeared between what was “male” and “female.” I learned that there must be hard, clear boundaries between gender and sex or our entire society falls apart. We have to be able to know what gender a person is by looking at them for less than a second. If we have to guess, or it’s not instantly obvious, than that person is obviously a pervert.

This was brutal on my personal development because I was growing up in the Quiverful South. Even though I fit into a lot of “girly-girl” stereotypes of American culture, I did not fit into the “lady like” stereotype I was supposed to be earnestly devoting myself to. I actively hated it, all while believing that I must be that way in order to be following God. I didn’t exactly have a lot of options. I spent most of my teenage years being taken aside and lectured by most of the women in my church. There would be whole Sunday school lessons devoted to the “womanly arts,” and the other three girl would be looking at me sideways because I was the only girl in that room who “needed to hear it.” When I would play with the other children and teenagers at homeschool meetups, I would be heavily berated by the other teenagers for wanting to be a soldier or a pilot in the war story we were acting out instead of the girlfriend back home pining away for her love. For a while I would fight for it, but . . . I started giving in. Ok, and I would admit in defeat. I’m a girl, I guess I should go pretend to be a secretary.

When I eventually decided I was going to college, several of the women at church told me that they had “washed their hands of me” and that I was basically doomed. I was never going to be a godly woman if I kept doing things like believing that I deserved an education and did not submit to my proper place below men. It was “feminine pride” and it would be my downfall.

However, when I getting ready for college, my mother decided that I was going to eventually decide I wanted to wear makeup, and since I knew absolutely nothing about it, she bought me Face Forward by Kevyn Aucoin. I didn’t even crack the spine my freshman year, but it turned out she was right– I did eventually decide I wanted to understand this whole “makeup” thing.

When I opened the book, I swear, magic dust must have fallen out of it.

At first, I was fascinated by the amazing transformations he was able to accomplish. He took pretty-but-still–normal-looking-women and created movie stars. It was amazing, and it made me feel powerful. I learned I could do the same thing on my own, although with much subtler effect. I could make my lips look poutier, or my eyes more cat-like. I thought it was incredible, and played around with “make overs” for many of my friends.

The back half of the book, though . . . initially, I didn’t go anywhere near it. Kevyn devotes a huge section of his book to incredibly dramatic make-ups, making over Susan Sarandon as Bette Davis and things– which was amazing how skillfully he did it. And then I turned the page, and staring up at me was Amber Valetta:

made up to look like both Clark Gable and Carole Lombard.

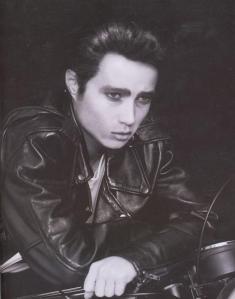

A few pages later, and Gwyneth Paltrow was James Dean.

Another page, and I saw someone named Alex who Kevyn had transformed into Linda Evangelista:

At first, my years of gender essentialist beliefs kicked in and I avoided the back of the book like the plague. I couldn’t force myself to go anywhere near that– but what else could you expect from a male makeup artist? Obviously something was very wrong with him, for him to be in a career that should only appeal to women. That’s why he’d done that. Because he was fundamentally unable to see the world properly. See? That’s what not having a Christian world view will do to you. You won’t see how clear and purposeful God was in creating two very separate, very distinct genders.

But . . . there were moments when I would go through those pages and stare. And I would feel horrible, wracked with guilt, and I would tell myself it was just morbid curiosity. That was it. I wasn’t feeling drawn to those images. There wasn’t anything there that was speaking to me in a way I couldn’t understand. No.

Eventually– a very long eventually— I started seeing those pictures the way 11-year-old-me would have seen them. As interesting. As powerful. As a very basic identification that we are maybe not as different as I’d been taught to believe. That I wasn’t limited by the “female role” that was being ascribed to me– that I could stretch beyond those requirements and figure out who I was and what I wanted independent of what sex or gender I “belonged” to. I could explore the parts of myself that weren’t ladylike. I could be proud of the characteristics I had that were “masculine.” I didn’t have to be ashamed.

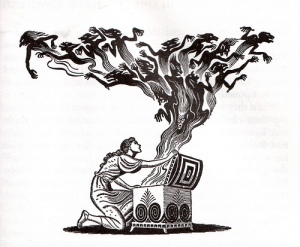

So, today, when I see artists like Maaria re-imagine a whole world by asking the question does Harry Potter need to be a boy and create astounding art:

I’ve learned to appreciate both the question they’re asking and the statement they’re making. They’re pulling us into a world where everything doesn’t have to be the way we’ve always believed it is– that we have the power and ability to change and grow and be something more.