[art by papermoth]

Today, I’m covering pages ix-xii from this edition of Captivating: Unveiling the Mystery of a Woman’s Soul, the introduction.

Last week, some of you said that you’d like to read along with me, which I think is fantastic. When you comment with your own thoughts on this section, write “Book Club” in the first line of your comment, then hit return/enter, just so it’s clear who’s commenting on the book itself and who’s commenting on my post (although your comments can be a mix, of course).

It is obvious, all throughout this book, that John and Stasi are trying, diligently, to avoid the pitfalls of other Christian gender-specific books. Stasi makes it clear that what she wants to communicate to her readers isn’t another “book about all the things you’re failing to do as a woman,” that she doesn’t want to give us another list of things to do in order to achieve “godly femininity.” She acknowledges that there isn’t only one way to be a woman, that there are Cinderellas and Joan of Arcs and neither one is necessarily the way to go.

However, struggle as they will to avoid those pitfalls, they can’t help falling into them:

Writing a book for men was a fairly straightforward proposition. Not that men are simpletons. But they are the less complicated of the two genders trying to navigate love and life together. Both men and women know this to be true.

…

How do we recover essential femininity without falling into stereotypes, or worse, ushering in more pressure and shame on our readers? That is the last thing that a woman needs. And yet, there is an essence that God has given to every woman.

I’m sorry, I do not know any such thing. My partner, a cisgender male, is exactly as marvelously complex as I am. He is interesting, dynamic, full of nuances and surprises. He is a human being, and that makes him complicated. Over the brief two years we’ve been together, I have found that every single element that could possibly be attributed to the “men are simple, women are complicated” stereotype is due to American culture.

His interactions with other men may seem to be more “straightforward” and “less complicated” because a) anything that could make male interaction “complicated” is read as “feminine” and thus suppressed, and b) we are trained to see male interactions and male behavior as normal, and female interactions and female behavior as deviant and abnormal. Being male is the standard through which we evaluate whether or not something is “simple” (and thus male), or complicated (and thus female). Because of this reality, it’s not that our interactions, feelings, and lives are more or less complicated, but that we are taught to evaluate all of these things through the lens of the male experience. Our dominant social narratives have been constructed, almost exclusively, by rich, white men– and because that male viewpoint is the one we absorb on a daily basis, of course it’s going to seem “simple” while viewpoints that differ from it are going to seem “complicated.”

For example: men simply “duke it out” in order to solve conflict, right? Of course, I’ve never actually seen that in action– in my experience, boys and girls were equally as likely to get into a physical tussle. There were girls who did not like violence, and there were also boys who did not like violence. The difference was, the girls were culturally rewarded for this dislike, while the boys were punished for being a “sissy” (a word that derives from “sister”). As mature adults, men solve their differences the exact same way women do– through communication. I’ve seen people approach conflict resolution in a stereotypically “feminine” way, and I’ve seen it done in a “masculine” way– but the people involved could be men, women, neither, or both. Both approaches, however, had the same elements if the situation was resolved and relationship restored– the communication included honesty, humility, and respect from all parties.

By embracing gender essentialism, Stasi and John have set themselves up for inevitable failure. If your basic assumption in beginning a book is that men and women are inherently and drastically different from one another and that these differences are not caused (or even exacerbated) by culture, then you cannot escape the conclusion that at least some of the “stereotypes” that Stasi finds so damaging are true, and based in an unassailable reality. If you believe that God has given every single last woman on the planet the same “heart” and the same “desires” regardless of race, ethnicity, culture, upbringing, sexuality, social class, and education, then you are working from a list of “10 things to be the woman you ought to be,” which Stasi condemns as “soul-killing.”

Sometime between the dreams of your youth and yesterday, something precious has been lost. And that treasure is your heart, your priceless feminine heart. God has set within you a femininity that is powerful and tender, fierce and alluring. No doubt it has been misunderstood. Surely it has been assaulted. But it is there, your true heart, and it is worth recovering. You are captivating.

It is paragraphs like that one that show me exactly why this book has been compelling to so many women– as a thought, it’s beautiful. She’s telling me that I am fierce and powerful and beautiful– it is a similar sentiment to what I tell my friends in order to encourage them. I like thinking of myself as fierce (and since Fascinating Womanhood, “competent” has become one of my favorite compliments).

But there’s a problem, even here. Not all women are feminine, and this is not because their “femininity” was lost, damaged, or assaulted– or that they’re burying it because they’ve been hurt, as Stasi will claim later. I am a cisgender woman– I identify with the gender I was assigned at birth. Most of the time, I “present” or “express” as “femme.” These things, my supposed “anatomical” sex, my gender identity, and my gender expression, are not the same thing. While I have never struggled with my identity, I have often struggled with my gender expression.

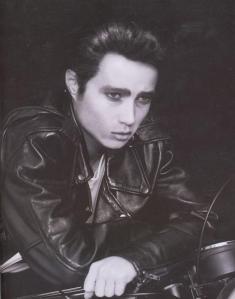

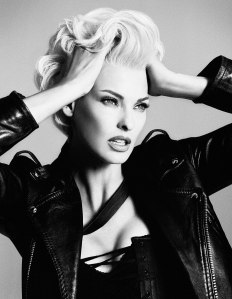

For example, these two images are of the same person, Gwendolyn Christie, who plays Brienne of Tarth on HBO’s Game of Thrones adaptation of Martins’ A Song of Ice and Fire:

On the left, playing Brienne, Gwendolyn is shown with a host of Western-culture masculine signifiers– armor, sword, short “undone” hair, grimness, and the masculine parts of her stature/musculature are exaggerated. On the right, though, she is wearing glamorous makeup, her hair is long and angelically flowing, and her facial expression is evoking something more stereotypically soft and feminine.

Then there’s things like Meg Allen’s photography project. As far as I’m aware, all of these women are cisgender (please correct me if I’m wrong), but none of them present as femme. It’s even possible for a non-binary person to choose to present as femme if they/ze want (see @themelmoshow and @awhooker –they’re incredible).

Insisting that there is something “essential” about a cisgender woman’s heart, and part of this “essentiality” is femininity is problematic in a variety of ways, but it contributes to the culture that allows transphobia to flourish. It’s part of the culture that allows trans women of color to be arrested for walking down a street and for trans men and women to be one of the most vulnerable populations in the world.

It also perpetuates the kyriarchal systems that force men and women to conform to a rigid set of gender-coded images, signifiers, behaviors, and interactions and refuses us all the ability to explore who we actually are.