A little while ago, I watched Matthew Vines deliver an hour-long message on all of the passages in the Bible typically use to condemn gay men and women. It was a beautiful message, and I highly encourage all of you to listen to it when you have the time. Hopefully it will be encouraging– and challenging. But, one of the things he said that’s really stuck with me is the way he talked about Matthew 7:15-20. I was practically raised on the Sermon on the Mount, so Matthew 7 is a passage I’ve heard before, many times. However, the way I’d grown up meant that there was only one possible understanding of what Jesus meant by “false prophets” and “wolves in sheep’s clothing.” A false prophet was many things, but it all essentially boiled down to someone who wasn’t a fundamentalist like we were. And they talked about good fruit and bad fruit, but they never really explained what it meant. I sort of made the connection between good fruit and the Fruits of the Spirit, but “fruit” usually meant “how many people you’ve convinced to pray the Sinner’s Prayer in front of you” . . . so, it was a bit of a tangle, for me.

However, Matthew Vines pointed out something, and it helped the light turn on for me. If the whole of the Law and the Prophets and Jesus’ ministry is Love God with all your heart and your neighbor as yourself, then it stands to reason that the difference between good fruit and bad fruit is love. If an interpretation of a passage, if a doctrine that you hold to, does not encourage you to love your neighbor as yourself, then it’s not good fruit.

St. Augustine put it a bit better:

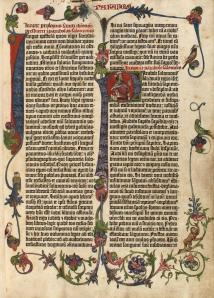

“Whoever, then, thinks that he understands the Holy Scriptures, or any part of them, but puts such an interpretation upon them as does not tend to build up this twofold love of God and our neighbor, does not yet understand them as he ought.”

On Christian Doctrine

This seems like a really good starting place. Love.

And, as I’m working through how I think, what I believe, and how I work with the Bible, figuring out how it should be a part of my life, there’s a few things that I’m reaching for. Yesterday we had an amazing discussion about sola scriptura and how we handle Scripture (seriously, you guys, it was spectacular), and some of you articulated some of the things I’ve been mulling over. There’s one comment in particular I’d like to share, since InsanityRanch put it so well:

First, both Jews and Protestants have what you might call a “democratic” tradition of Bible reading. That is, the Bible is not the sole province of an educated elite. At least in theory (and largely in practice) everyone is supposed to study the Bible . . .

That said, there are some interesting differences as well . . . . [One being that] Jews read Bible with commentary. When I first started reading the Torah, I read it with Rashi (11th c. genius commentator on the Bible and Talmud.) The idea that the text of the Bible is free-standing is profoundly unJewish. There are layers and layers of commentary, so interwoven that it’s impossible to read a Bible passage without also thinking of the various strands of commentary on that verse. One has a sense of the different ways the verse has been read through a long history. Reading in this way makes the text seem very much less cut and dried, less susceptible to a single, simple interpretation.

As a consequence of reading with commentary, Jews have read in community, and the currency of community was questioning. Any interpretation offered for a verse tended to evoke a challenge, with one reader arguing according to R. So-and-so’s commentary and another reader arguing according to R. somebody else. This process made it hard to hold calcified interpretations of textual meanings… though of course, not impossible.

I think the idea of reading in community is paramount, and I think this is something that has been lost– or perhaps never present, I’m not sure– in evangelicalism and some Protestant environments. We gather together in church on Sunday, sometimes we do Bible studies or small groups together, but that’s about all we get in community, and it’s somehow separate from how we read Scripture. It seems that there’s been a strong emphasis in evangelicalism on “reading the Bible for yourself” that the result has been a highly Individualistic approach to Scripture. Somehow, though, instead of this resulting in what InsanityRanch described above, it seems that the Modernism so entrenched in evangelical philosophy results in us putting consensus above all other goals. There’s only one right way to interpret a passage. And, in America, with our individualism and exceptionalism and the fact that the evangelical church is so politicized, we wind up with that “one right way” usually feeding into a really harmful and dangerous status quo.

Being willing to embrace the possibility of not knowing when it comes to our Bibles is discomfiting. But, understanding that the Christian faith is not supposed to exist in isolation, but in community,I think could be a really strong first step.

All of this has somehow led me to re-evaluating a deeply ingrained belief that I’ve grown up with, a belief that seems to be synonymous with Protestantism and evangelicalism alike: that Scripture is the final authority, that Scripture alone is all we need to live our faith. And regardless of how the Reformers originally meant this (since Luther himself believed that some parts of Scripture don’t need to be listened to coughcough James)– what it has come to mean in evangelicalism could be encapsulated in the phrase “God said it, I believe it, that settles it.”

In the theology course I’m taking, they present a concept called the “Stage of Truth,” which some of you are probably familiar with. Some traditions present this similarly to the Wesleyen Quadrilateral, except the Stage of Truth is more prioritized and hierarchal than that. In Protestant and evangelical sola scriptura traditions, the Stage of Truth looks a bit like this:

Scripture, of course, is at the head since it is the final authority in a Christian’s life. But I’m looking at the other elements on this “stage,” and I’m wondering about a good tree cannot bear bad fruit and I’m looking around at the world around me, and I’m wondering if something like Experience or Emotion doesn’t belong closer to the front.

Because in my lived experience, I’ve felt the horror of Deuteronomy 22 being the final authority in my life. I’ve felt the full, brutal weight of the fact that Scripture doesn’t have bodily autonomy or individual agency well articulated in its pages, and I know what that does to a person. I’ve spent most of my adult life (what little there is of it) struggling under “biblical patriarchy” and having to fight with all of the voices screaming at me that being on my own is rebellion against my father. I’ve been depressed and been told that I must “take every thought captive” and that “perfect love casts out fear” and that I’m just not loving God enough, that’s why I’m sick.

And all of these ideas have come from having a “high view of Scripture,” and believing that what it said had complete authority over my entire life. That I had to force myself into alignment with the “clear teaching of Scripture” because it was the only authority I had. If the Bible had something to say about an idea, well, that was what I had to believe. That was the opinion I had.

I didn’t know that all of that was heavily predicated on interpretation, on the fundamentalism I was raised in, that it wasn’t the Bible but an interpretation of the Bible– but thinking like that was actively discouraged by everyone I knew. Pastors and evangelists and missionaries and Sunday school teachers and professors and Bible study leaders and speakers and teachers all telling me that This is what the Bible says This is what the Bible says and somehow they all sounded the same so I believed it.

And it wasn’t until that I understood that my life matters and my experiences matter and what I feel about people matters that I started re-examining what the Bible so clearly says. When I placed my Bible in tension with my life, and the people I care about, and what I can reason to be true, what so many before me have observed to be true, some things became a lot more simple. It wasn’t until I’d set aside my “high view of Scripture” that loving my neighbor really became possible.