Today’s guest post is from one of my amazing readers, Airmid. “Learning the Words” is a series on the words many of us didn’t have in fundamentalism or overly conservative evangelicalism– and how we got them back. If you would like to be a part of this series, you can find my contact information at the top.

Having grown up in a very conservative homeschooling family, I remember certain areas in which it was simply accepted that we were right and everyone else was dead wrong. It was an atmosphere that distrusted everything conventional. Education, medicine, nutrition, politics… we believed most people were wrong. Possibly it was deliberate, possibly they were all just deceived, but either way, the conventional wisdom could never be accepted.

One of the areas where I remember this being most strongly expressed was anything remotely related to psychology. Even Christian psychology was regarded with great suspicion, and not to be trusted because psychology itself could not be trusted. In fact, I remember seeing a commercial—a rarity in and of itself, because it meant the tv was on—for a Catholic hospital advertising a treatment for depression, and the response from my mother was “it’s so sad that they proclaim the name of Jesus but aren’t offering the true solution.”

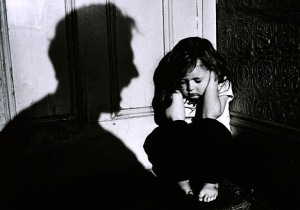

Contributed to by a number of complicated factors including family tragedies, being very overweight, and probably a genetic predisposition on both sides, I experienced several severe episodes of depression as a teenager. One in particular, lasting a year and a half, is the time I refer to as living in a black hole.

Thing is, I have to assume it was depression then. Even though I had most of the symptoms and almost certainly would have met the criteria for a diagnosis, I don’t know what to call it because I was never allowed to look for help. The message I received, whether intentionally communicated or not, was “You chose this. Yes, tragedy may have happened and you had a right to be sad for awhile, but snap out of it and pull yourself together. Don’t you see the shame you’re causing us? You have no right to be depressed. You’re just angry at God.”

And to a certain extent they had a point. To a certain extent, I was choosing to hang on to the depression. To a certain extent I was angry at God. To a certain extent. I thought it was the only thing that made me me. Looking back, I have to wonder how your child believing depression was her identity and she had to hold onto it or lose herself was not cause for even more serious concern than simply depression in and of itself.

I want to go back to the thought “you have no right to be depressed.” I believed that. I believed I had no right to the name depression and no right to call it a disease outside myself. I believed that I was at fault for being depressed because I “chose” it. Because that was the message I had always received. ADHD and every other behavioral disorder out there? Maybe real. Some of them. Certainly over-diagnosed. Depression? Suck it up and look on the bright side. Anxiety? You’re not trusting God enough. All these disorders weren’t nearly as real as the world was making them out to be. They’re taking sins slapping a label of “disorder” on them, and suddenly the treatment isn’t discipline or prayer or trying harder and being less selfish, it’s just medication.

In some rare cases, there might be a valid point there, but all it ever did was hurt me. That mindset told me that I could never actually have a disorder. Whether it was intended or not, the message I got was that it was all my fault. Many years later, having been clinically diagnosed with an anxiety disorder and still strongly suspicious of clinical depression as well, causing my college years to be their own version of hell, I had a conversation with my parents about the possibility of medication for treatment, since I was still a financially dependent college student. In response, my parents told me in the strongest terms imaginable that the idea was unthinkable and not only would they not support me, I would not be allowed in their house if I chose to take anti-depressants or anti-anxiety medication. They emphasized that accepting a diagnosis and seeking treatment would make the disorder me. Accepting the version of reality in which I was a person with depression and anxiety would make me identify with the disorders and they would become an inescapable fate.

And in that moment, I realized with utter clarity it was a lie.

Everything I had heard up to that point made the disorder my identity. The only thing to make it separate was naming it. A name set it apart. A name made it other and outside me. A name gave it an identity as something Not Me. And with a name, I could fight it.

Without a disorder, I was fighting an unknowable opponent in the dark. Or worse, fighting myself. With a disorder, strangely, I now have hope. Because something outside of me is something I can fight. Most of all, it’s something I can have hope of beating without destroying myself in the process.