If you’re a living person in Christian culture, then you’ve run into the following sentiment:

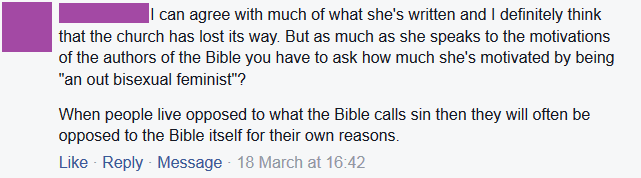

The argument goes that because we’re LGBT (or, in this particular case, also a woman who believes in equality), we have “skin in the game” of biblical interpretation. Obviously we’re predisposed toward a particular outcome, so our judgment can’t be trusted. We can’t possibly read the Bible “objectively,” so any argument that a queer person makes about Romans 1 not necessarily being about sexual orientation is intrinsically untrustworthy.

Unlike straight people, who are clearly impartial and unaffected by this issue, so they can read the Bible without being influenced by their feelings. They can come to a clear-headed and open-minded conclusion on whether or not having sex with a similar-gender person is a sin, but a queer person can’t. In short, straights are telling the LGBT community that they definitely have our best interests at heart, and they can totally be trusted not to be wrong about this.

Aside from how incredibly patronizing this attitude is, we also have some fairly definitive proof that straights do not have the best interests of the LGBT community in mind. I know that in their head, they do– I know that they’re probably aware of how their “support” looks to us. They also don’t really care. To them, all that matters is that we’re saved from our sinful lifestyles; if they have to support legislation that will harm trans people, or force destructive conversion therapy on LGB youth, or encourage parents to physically beat their children into being straight, or call for us to be stoned to death … then they will. They have to hold us accountable for our sin, and if they kill us (or encourage other people to kills us) in the process, then no matter.

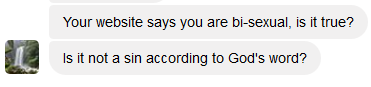

And even after countless decades of the Christian right condemning our very existence as sin, like this fellow:

… we’re just supposed to accept that straights don’t have any possible motivation that could affect their judgment. They don’t have feelings about us that could make it difficult to be impartial. No ounce of hatred, no sliver of fear. No revulsion or disgust whatsoever. They approach LGBT rights and the Bible as a blank slate, with no predispositions of any kind.

Oh, except that’s completely wrong. In fact, people like Thabiti Anyabwile have explicitly argued in favor of Christians depending on their disgust (which is, needless to say, an emotional reaction) to drive their morals and biblical interpretation. Listen to Kevin Swanson and his ilk bloviate for more than two seconds and their hatred of us comes searing through.

Sure, maybe I’m being affected by my desire for love and acceptance when I read Romans 1 … just like any straight person can be affected by their disgust or hatred or fear when they read Romans 1.

The fact of the matter is that, when it comes to the Bible, no one is objective.

I came to the Bible a few years ago, doing my best to be open and honest about what I would find. To be blunt, my thinking at the time was that if I discovered that the Bible does speak on sexual orientations and condemned similar-gender relationships, then I was going to walk away from it all and leave Christianity behind. I knew I was bisexual, and if the Bible was going to tell me that was wrong, then I was done. Obviously, I’m still here, so I must’ve discovered something different. In my opinion there isn’t enough evidence one way or the other to be absolutely conclusive, so I err on the side of loving others and doing no harm. My hermenuetic looks a bit like St. Augstine’s, actually:

Whoever, then, thinks that he understands the Holy Scriptures, or any part of them, but puts such an interpretation upon them as does not tend to build up this twofold love of God and our neighbor, does not yet understand them as he ought.

This argument that only straight people can be trusted to interpret Scripture correctly and appropriately– because queer folk don’t want to be told we’re sinning– doesn’t make any sense. If it were true, then no one would ever be able to agree about any sin. Except we know that it’s possible for greedy people to know they’re greedy and that the Bible vociferously condemns it. Or how about the two sins that almost always get brought up in these conversations: pride and gluttony. I’ve known many people over the years that confessed to gluttony and acknowledged their belief that the Bible says that gluttony is a sin– and the same thing goes for proud people.

If straights are right about the LGBT’s supposed inability to “properly” read the Bible, then how in the world is it possible for anyone to read the Bible and feel challenged by it? Our personal experience tells us that it is not just possible, it happens all of the time. I still experience feeling “convicted,” to use the evangelical parlance, and I don’t even think the Bible is inspired or inerrant anymore.

We all bring our baggage to the Bible. That’s part of what makes our collective experience of it so beautiful. It’s a text we share communally and individually, publicly and privately. We talk, we share, and together we try to build an understanding that enriches our lives, brings us comfort, and helps us to act justly, love mercy, and walk humbly.

LGBT people shouldn’t be shut out of this conversation anymore. We bring a different set of experiences, a different way of being, a different way of seeing. When you silence anyone who isn’t white, or isn’t straight, or isn’t nuerotypical, you’re shutting yourself up into an ivory tower. It’s impossible to cut off the parts of us that make us human and still do good and loving theological work.

In my life, being bisexual puts me at a certain distance from the Bible because I’m not deliberately included in it. Because of that, my relationship with the Bible has to be more interrogative than it would otherwise be, because it’s a story we’re supposed to find ourselves in. When it’s not obvious where I fit, I have to do more digging. I’m open to discovering things that aren’t sitting on the surface. In a sense, I can benefit from the fact that I’m not the primary audience– often, I’m an outsider looking in. I can help broaden some of the narratives, bring stories into new lights and next contexts.

I can look a story that we’ve all heard a thousand times and ask questions like is it possible that Ruth is bisexual? When she abandons Moab and aligns with Noami in a speech that is often used in our wedding ceremonies; when she lives with Naomi, comforts her, listens to her, and raises a son with her … do we have to view her character as straight? Why do we assume she’s straight?

Because I don’t have the dominant experience of heterosexuality, I’m better equipped to get at the bottom of some of our assumptions. It’s my first impulse to ask why of concepts that seem long settled.

I lack objectivity. So do you. And that’s a good thing.