I was so proud when Christina asked me to go with her to a revival service in Alabama. Her family regularly traveled what I thought of as “great distances” in order to be “ministered to by the Word.” But she had never asked me to one, and I happily said yes. Excitement mounted as it came closer– this was supposed to be a “good ol’ fashioned tent meetin‘” and I was picturing things like ladies in bonnets and “chicken on the ground.”

We arrived on the “campground,” and there was a gigantic tent set up with rows and rows of metal folding chairs. A generator was beating away somewhere just to run the huge fans and audio equipment. As evening fell, it got darker, but not cooler. It was Alabama in the middle of a sweltering summer. But, I was enthralled by the mystery of it all. Here was where a great thing would happen, I just knew it– like those boys who prayed in a hay stack and started the Second Great Awakening.

We sang all the old “revival hymns” and then settled in for the preaching. I don’t really remember what the sermon was about, although it must have been about sin because of what happened in the middle of it. The evangelist called a man up out of the congregation, and I watched him walk up the dirt aisle to the front. As he passed me, I stared at his eye patch and wondered if he was Patch the Pirate. When he got up to the front, the evangelist asked him to share his testimony.

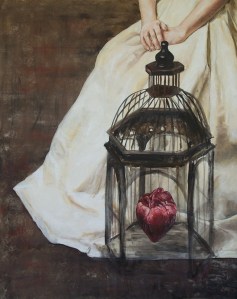

Slowly, the man shared his story of a lifetime of sin and abuse, but he culminated by telling of his addiction to pornography. He concluded his tale by lifting his eye patch and telling us that he had followed Matthew 5:29, where it says if your right eye offends thee, to pluck it out. He, in obedience to God’s word, had done just that– and thus, God gave him the strength to overcome his addiction.

Clearly, I did not pay attention to the rest of the sermon. I remember just sitting, dazed, through the rest of it, because I knew if I one day ended up struggling with a sin like that, I was not going to gouge out my eye. I struggled with feeling “convicted” the rest of the sermon. Shouldn’t I be willing to do whatever it takes to obey God? How much more should I value my relationship with him and having a pure heart over my fleshly pleasures? Over trying to avoid pain, and protecting myself?

We came back, and I also don’t remember what the evangelist preached the second night because of what happened. A few minutes after he had started preaching, there was a slight commotion. I don’t remember exactly what made me turn around, but when I did, I saw a black family sitting down in the remaining seats in the back. I didn’t think anything of that and turned my attention back up to the front– where the preacher that had organized the meetin’ was standing up.

“You!” He yelled, striding boldly to the back of the tent. “Yes, YOU!” He pointed. Suddenly, I realized that he was gesturing at the black family. “You don’t belong here. Here,” and he flayed his arms wildly over the throng gathered under the tent folds, “is the bounds of OUR habitation. These are OUR borders. You just get– get back to where you belong, boy. You’re not welcome here.”

“Amens!” and “Preach it, brother!” started echoing from all over the tent.

And I watched, horrified, as the father stood up. For a moment I could see rage engulf his face. Cords tightened in his neck, and I watched as his fist clenched. He was trembling, and I knew it wasn’t in fear. But, after a long moment, he reached down for his wife’s hand. He pulled her up, then turned and picked up his daughter. He faced the preacher again, his daughter in his arms, but then didn’t say anything. He just . . . left.

As they walked back out into the night, the hollers and jeers came to my ears like they were traveling through water. I couldn’t believe what had just happened. I remember looking down at my hands and watching them shaking– trembling violently. And I couldn’t identify the emotions that were rampaging through me. I glanced over at Christina and her father– but their faces were impassive. They didn’t seem to be affected by what had happened. I looked around the tent, and saw that some were gathering up their families and leaving, and I could see anger mixed with disappointment on their faces. The evangelist and the preacher screamed after them as they left, calling upon every biblical invective I’d ever heard.

The evangelist returned to his sermon eventually, but after ten, maybe fifteen minutes of preaching, I couldn’t stand it anymore. I had to get out of that place. Christina grabbed my hand and asked where I was going, and I muttered that I had to use the bathroom.

I stayed in the bathroom as long as I could without Christina or her father wondering where I’d gone, scraping together my determination. I was not coming back to this place. I was not coming back, and I did not care what Christina thought of me.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

There is a term for what happened in those two examples, and it has actually been referred to as “the evangelical heresy” (and no, I’m not talking about individualism). It’s called biblical docetism, and it is an extension of gnosticism, dualism, and Arianism. All of these systems promote a common thread that “physical” things represent evil, as they are corrupted copies of the pure, “spiritual” realm. Dualism eventually leads to a mind vs. body dichotomy. Arianism teaches that Jesus was not truly incarnate– he only looked like or seemed to be physical (the term docetic comes from the Greek word dokein, “to seem to be” ).

Biblical docetism is an approach to understanding the inspiration of scripture. There are many perspectives on this, including “verbal plenary” view and the “degree” view, among others. People who hold the docetic view– and many of them have no idea that this is what it’s called, I sure didn’t– all tend to ignore the human component of scripture. They see the Bible strictly as “the Word of God.” Some consequences of this view are:

1) Being able to randomly select any passage of scripture to see how God will speak to them. This includes being able to draw huge spiritual implications out of simple things like Paul asking Timothy to bring him his cloak in 2 Timothy 4:13. And yes, Spurgeon, I’m looking at you.

2) Believing that every single scripture applies to everyone, everywhere, and always. Including 2 Chronicles 7:14, which is used to support Dominionism. And segregation. And all kinds of evil things like slavery and the oppression of women.

3) Believing that the chapter and verse organizations and the canon order are inspired, too. This is less common, but it happens among re-inspiration advocates. Let’s give a shout-out to Micheal Perl and Peter Ruckman, here.

4) Completely ignoring that the writers had personalities, preferences… or that they had anything to do with the Bible whatsoever. We can learn a lot about Peter’s impetuousness, or Paul’s logic, or Luke’s compassion, but that has no bearing on fundamentalists who see the Bible as only the Word of God.

5) There is no such thing as progressive revelation. Because God wrote it, and God is timeless, and God is omniscient, there isn’t any such thing, actually. God wrote Genesis, and God wrote Revelation. It doesn’t make a lick of difference that John the Revelator had witnessed the Resurrection and had some inkling about what was going on, and Moses couldn’t even really understand the Messiah. This can be disastrous from a hermeneutics perspective, because then you start assuming all kinds of things into the text that cannot sensibly be there.

6) They pay absolutely no attention to genre. At all. Every single element in the Bible is exactly the same as all the rest. There’s no reason to pay attention to the nuances between historical narratives and poetry, or biographies and epistles.

7) The supremely over-literalization of Scripture. I cannot stress this one enough. You cannot take the Bible too literally, or you end up thinking, saying, believing, and doing all kinds of insane things. Like plucking your eye out when you have a porn addiction. They have no understanding of metaphor, myth– they cannot account for different narrative structures. To them, every single parable Jesus told literally happened. They turn the entire Bible into a perverse form of itself– as dry and un-human as an encyclopedia.

And, most dangerously, because they believe in a non-fiction, give-me-the-facts-ma’am approach to the entire Bible, they prioritize imperative statements over anything else. They reduce the beauty of the Bible down to a bunch of commandments and lists. They take the suggestions that exist inside an over-arching narrative and force them to be the filter for everything else. And this fails us, because the Bible is a book of story before it is anything else. It gives us story after story— and nothing about these stories in inherently prescriptive. They describe human beings in all their glories, triumphs, and absolute failures.

And when you believe that miniscule imperative statements trump entire narratives, you miss out on the complexity that is woven into scripture. You lose stories like Deborah and Junia and Phoebe and Tabitha and Lydia and Anna and Priscilla– because these stories about powerful women conflict with the limited suggestion of one author to one friend. You lose the ability to learn from the value of contradictions, because instead of recognizing contradictions as the human component of individual perspective and human narrative, the contradictions become something you have to explain away or deny.

And that traps us. It limits our ability to learn, to grow, to understand, to seek, to question. Dichotomies, dualities, and binaries come into play– with only one being “right” and anything else being “wrong.” We lose the ability to appreciate a modern narrative of multiples views, multiple understandings. We lose variety and complexity. And, looking around outside, our world is nothing if not complex.

(My list of seven consequences of biblical docetism was structured for me by Bibliology and Hermeneutics.)