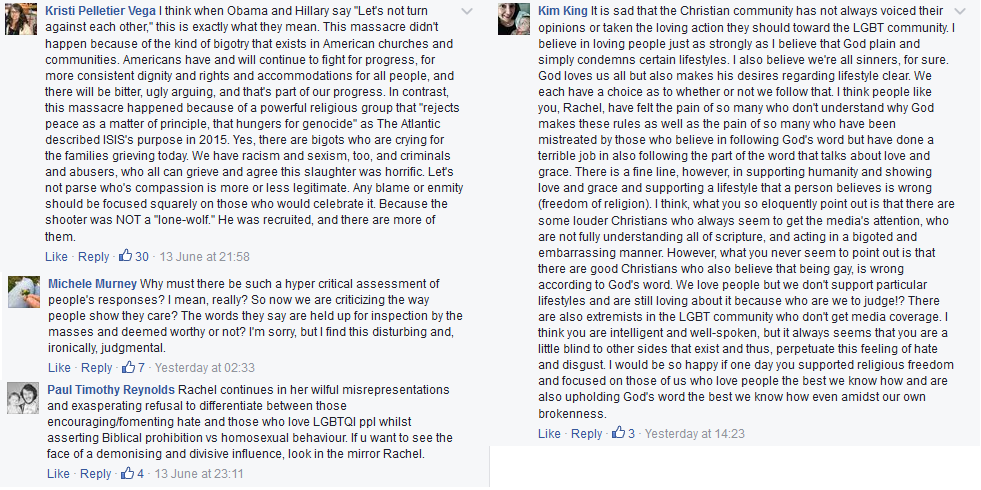

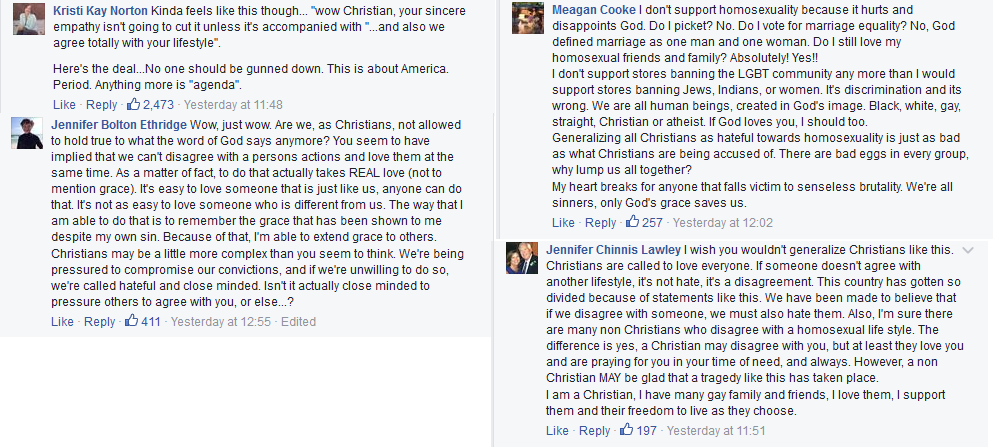

For almost a year I’ve been dealing with the aftermath of finding out that people I know hate me. I had to look in their eyes and see nothing but rage and disgust at my very existence. It’s been difficult in a way that few things have been, in a way I wasn’t able to articulate until recently.

***

I hate someone, too. The man who raped me. The fact that he exists, that he is out there, somewhere, carefree and happy and free while I’m burdened with everything he did to me… it fills me with fury. I am disgusted by him, by what I know he’s capable of doing. The fact that he can still suck air into his lungs and be filled with life makes me want to retch because I can barely stand the thought that I am utterly helpless to stop him from hurting other people.

I’ve done the one thing I can– I reported him to the police. Hopefully when he hurts another girl, another woman, if she decides to go to the police there will be a report there saying you’re not alone, he’s done this before, he deserves to go to prison, and we can send him there.

I hate him. The world would be a better place if he weren’t in it.

***

It was hard looking into someone else’s face and seeing that feeling there, directed at me. To see hatred for everything I am as a person, everything I represent, flickering at me in their eyes. Wishing for my disappearance, my non-existence. Not that they want me dead exactly– just to have never existed in the first place.

It’s a different sort of hard than the banality of hatred I encounter almost daily. Lots of people think I’m uppity, or selfish, or a liar, or stupid, or fat, or unattractive– and have told me so, as loudly as they can manage through a keyboard. There are people out there who love to pick me apart or whip up angry, pitchfork-toting mobs. While occasionally frightening, and certainly disruptive, mostly it’s simply a matter of time before I can set it aside and not let if affect me. I don’t have to pick up any of their labels and carry them around with me. If someone calls me stupid, the only reaction that calls for is laughter. If they call me a liar, well– I know I’m telling the truth, and that’s all that really matters.

But when someone you know reacts to your presence in the room with loathing it’s not possible to just set it aside. It’s not some ridiculous accusation hurled in your direction over the internet for you to ignore and delete.

If you’re a good, decent person, and someone looks at you like that, your automatic question is going to be what did I do? People typically have very good reasons for their hatred and disgust. I hate a rapist because of what he did to me, and what I’m afraid he’ll do to others. So, of course, the natural impulse will be to try to figure out what you could have possibly done to provoke that reaction.

When the answer is “you exist,” it’s devastating.

If you’re a good person, you want to try to fix whatever you’ve done, or change it. You want to undo whatever’s happened and earn their forgiveness– because irrational and bigoted loathing simply doesn’t make any emotional sense. You can objectively know that bigotry exists in the world and there’s not a whole lot you can do about it, individually, but then you encounter it in someone you care about and what you objectively know doesn’t matter as much as trying to do everything you can to make them stop hating you so much.

Queer people encounter this in our friends, our family, our churches, our communities. We can feel all the revulsion directed at us, and our reaction is so human. We want to fix it– and it’s not like we haven’t been told how. Lie to yourself, lie to us. Let us electrocute you. Take this mountain of shame and self-loathing and carry it on your back wherever you go. Never love anyone the way Christ loves the church or Jonathon loved David or Ruth loved Naomi. Deny every chance at romantic happiness. Never have a family.

Do it all alone, because we certainly won’t help you.

Many of us have tried. Many of us have died trying. I certainly tried for most of my life– and was somewhat good at it, too. Until the moment I realized that being queer makes me incandescently, buoyantly, happy. Until I met someone that didn’t force me to lie to him in order for us to be together– who finds as much joy in my queerness as I do. Until I discovered acceptance among my queer family in a way I’d never felt before. Until I discovered that I can feel pride in who I am and what I bring to the world as a queer person.

I had the chance to let my burden fall off my back and tumble away, and I will never go chasing it down. Not even if all the dishonesty and deceit and duplicity in the world could wipe away the disgust I see in their eyes. It’s just not worth it, however much their hatred hurts. I’m not going to stop existing to make anyone else more comfortable. I will not light myself on fire to keep you warm.

Love isn’t the thing that needs to change. Hate is.