The night before I left for college, I was a gigantic mess. I was all packed, all ready to go, when I about had a meltdown and my mother stayed up with me late that night trying to talk me out of my tree. I was panicking– absolutely positive that college was going to be nightmarish, that I was going to fail every class, and that I would never be able to adjust to a classroom environment.

Turns out, most of that worrying was for nothing. I did well in the general education courses– although I strongly suspect that it was almost entirely due to the fact that the 101 classes at this college used the exact same textbooks as what I’d used for 12th grade, so we were literally going over the same exact material. When all the review questions from the textbook are the same, turns out the tests and quizzes are largely the same, too. Also, because I was at a fundamentalist college, the classroom environment is completely unlike what you’d see at most other colleges. I believe, looking back, that if I’d tried to enroll in a private or state school, I would have floundered. I might have been able to keep my head above water, but it would have been a struggle every day.

At this school, all seats are assigned– from freshman level all the way through graduate courses. I never experienced a class discussion the entire time I was there. Almost every class was lecture-based, with a few exceptions for “lab” classes that were essentially nothing more than homework review. Given that the environment was this structured, rule-following me actually fit in quite well. I didn’t have to guess at anything, or figure anything out. As far as class was concerned, there wasn’t any protocol that wasn’t explicitly stated.

Socially, my experience was . . . interesting. My freshman year, all of the friends I made were fundamentalist homeschoolers (well, one of them attended an ACE church school). However, even though we were all from similar backgrounds, shared similar beliefs, and were all at this college for pretty much the same reason, we discovered that interacting with other people our age independent of adult supervision is freaking difficult. There was constant bickering and in-fighting, and none of us knew anything about conflict resolution, which led to me abandoning them because I couldn’t stand having a relationship like that anymore. I thought these particular people were just “drama-filled,” but it really wasn’t that. They were struggling just as much as I was, and we didn’t know anything about how to form friendships that weren’t inside the homeschool paradigm. There was certainly fun times– there were reasons we tried to be friends– but in the end, it became too difficult to keep ourselves together. We splintered off, and kept touch with each other, but having a relationship failed.

We also didn’t know basic human realities like it’s impossible for some people to be friends, or that basing a relationship on “iron sharpeneth iron” would probably ruin it. There is some interplay happening between fundamentalism and homeschooling– I won’t deny that– but our homeschooling background was a contributing factor in our relationship difficulties; I would argue that being homeschooled exacerbated problems we were already guaranteed to have from our fundamentalist upbringing.

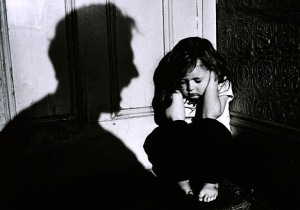

In conservative religious homeschooling (which, like the rest of homeschooling, is certainly not monolithic, but, again, there are over-arching patterns and commonalities), even for homeschoolers involved in co-ops and groups, socialization doesn’t just mean “interacting with people.” It doesn’t mean “have friends.” In an incredibly basic sense, “socialization” is the process of learning how to act in your culture. If I’m operating inside a fundamentalist religious culture, then I am incredibly well socialized. I know exactly how I’m expected to behave, what role I’m supposed to fill, what “language” to use, and what the societal expectations are. When it comes to interacting with American culture, though . . . I’m lost. And it’s not just that pop culture references fly over my head, that I’ve never seen an episode of The Simpsons and that I’m just now learning about things like hip-hop and Andy Warhol. It’s that I’m still struggling to understand what pluralism means, that Truth is largely inaccessible, that freedom of religion and freedom from religion are just as important..

I also don’t understand how to behave around my peers. I don’t know what constitutes “dominating a conversation” verses merely participating in it, and what the regular give-and-take of conversation looks like. I, like Sheldon Cooper, have no idea what the social protocol is for many situations. Conflict resolution? No idea. I don’t know how to establish and maintain healthy boundaries.

And, on top of that, I spent almost all of my life interacting with people who agreed with me about everything. I did not have the experience of having a conversation with a real-life person where we disagreed about anything significant until I was 23 years old. I was not exposed to people who had substantively different life experiences, who had different understandings of the Christian religion– let alone anyone who wasn’t a Christian. I didn’t meet an out gay person until I was 21. I still haven’t actually met someone who I knew was an atheist or agnostic in real life. I’ve yet to have a conversation with someone, in person, who doesn’t believe in some form of biblical creation. The most dynamic experience I’ve ever had was having a conversation with someone who is Neo-Reformed. After we joined the church-cult, I didn’t know anyone who wasn’t white, and nearly everyone around me was horrifically racist and Islamaphobic.

That’s what we’re talking about when we say that socialization should be a concern for homeschoolers. It’s not that homeschoolers are completely isolated (which they absolutely can be), it’s that socializing your homeschooler has to be intentional, and it is not easy or automatic. Going to church is not enough. Going to a co-op that’s basically the same environment as church is not enough. You have to go out of your way, parents, to make sure that your children are being exposed to ideas–political, philosophical, religious ideas– that aren’t the ones you believe in. You children need to grow up knowing Democrats if you’re Republican, and vice versa. They need to know someone who isn’t a member of your denomination. They need to understand pluralism from first-hand experience.

Because, the second they’re not a homeschooler anymore, the second that they’re struggling to survive in a world filled with multi-culturalism and reasonable arguments for virtually every idea conceivable, they might not be able to deal with it. They could give up on everything they were taught to believe. For many homeschoolers, that typically means Christianity and conservatism.

For many conservative religious homeschoolers, one of the primary reasons to homeschool is to isolate their children, to make sure that they’re not exposed to ideas that the parents find unhealthy or dangerous. You can’t try to do that and make sure that your children are well-socialized, too. They don’t go together.