This is an expository/interpretive paper I wrote for my “Interpretation as Resistance: Feminist, Womanist, and Queer Readings of the Bible.” I hope y’all enjoy it.

***

The whole LGBT movement is as phony as a three-dollar bill; look at this “B” thing in the middle; that’s just clear-cut straight-up promiscuity.

~Andrée Sue Peterson

The ‘B’ stands for bisexual. That’s orgies! Are you really going to support this?

~James Dobson

Rebuke your mother, rebuke her, for she is not my wife, and I am not her husband. Let her remove the adulterous look from her face and the unfaithfulness from between her breasts … She said, ‘I will go after my lovers, who give me my food and my water, my wool and my linen, my olive oil and my drink.

~Hosea 2:2-5

I thought that the redemptive love story of Hosea and Gomer was familiar to me. It was a metaphorical touchstone for the faith community of my adolescence, a story we referred to often as containing the Creation–Fall–Redemption arc we believed was at the core of Christianity. Gomer’s story was our story, because no matter how badly we sinned or how far we fell, God would still love and forgive us. Now, it is fascinating to me that although there are distinctive anti-Semitic tendencies in Christian fundamentalism, the way we interacted with Hosea was almost midrashic. This is demonstrated nowhere so well as in Francine Rivers’ Redeeming Love, which is a retelling of the story of Hosea and Gomer set during the California Gold Rush. However, attempts to give a narrative framing to Hosea exist in abundance—evangelical Christian-style midrashim of Hosea are at bible.org, Lifeway, and Christianity Today. These retellings were more familiar to me than the text itself, and had overwritten my understanding of Hosea so much that when I read it in the NIV and Tanakh Translation, I was surprised by how much I struggled to find the narrative structure I’d grown up with.

I have been deep in the trenches with the evangelical structuring of Hosea as I’ve been doing a close reading of Francine Rivers’ Redeeming Love for the past year. Over that time, the character of Gomer—and Rivers’ character, Angel—have come to mean a great deal to me for the exact reasons that Rivers, and evangelical culture more widely, condemn Gomer. My participation in this class has shown me that I love Gomer because I read her from a bipanqueer perspective, and in resisting Rivers’ framing I’ve come to play a Trickster role with the text. After all, if there’s a biblical character that evangelical and fundamentalist Christians would compare me, a bisexual woman, to—it’s Gomer. Gomer and I represent a sexuality that cannot be constrained, women who exercise our autonomy in defiance of societal expectations, and even if we arrive in a place that is culturally approved, we still represent a queer threat of instability.

In Hosea, Gomer is figurative of both women and Israel as a nation. After her introduction in the opening of the text, she is not referred to by name again. Instead, as the text develops she is replaced by generalities: woman, wife, mother, adulteress, prostitute, whore. Gomer’s badness is just women’s badness and Israel is bad when she/he/it behaves like Gomer (or like women). As a bipanqueer woman, I am frequently forced by culture to be a similar stand-in for all other queer women—or their ideas of queer women are forced onto me, regardless of their accuracy. There’s no separation of our “badness”; queer women are bad like me, and I am bad like queer women. The same thing happens in Hosea when the specificity of Gomer disappears from the text. Who she actually is doesn’t appear to matter to the writer(s), and telling her story is irrelevant. I intend to subvert this approach to the text by bringing the specificity of my story and to return Gomer as the principal character of the book.

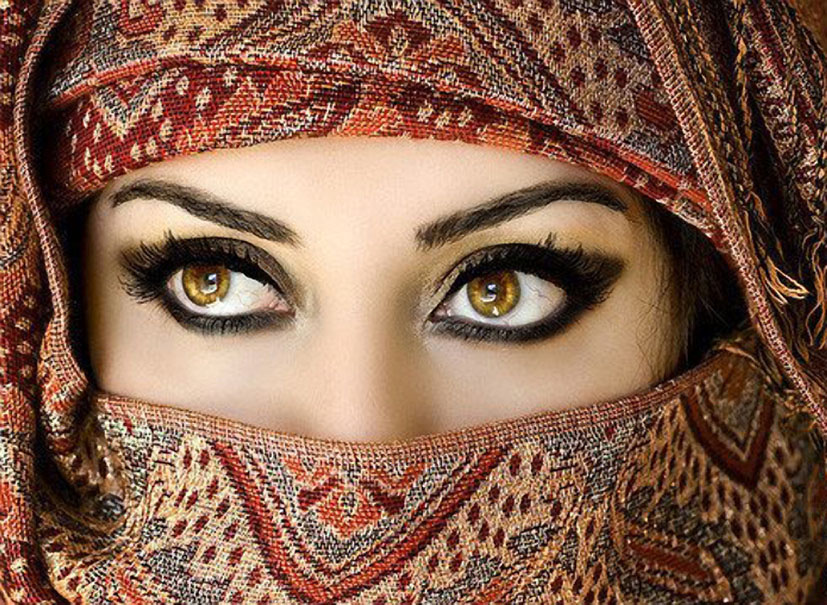

The writers represent Gomer as a woman whose sexuality cannot be controlled, restrained or limited. She is an adulteress, “burning like an oven … blaz[ing] like a flaming fire … devour[ing her] rulers.” In the evangelical narrative framing of her character, Gomer returns again and again to her old life, which is depicted as irresistible to her. All through the text she is described as having a “spirit of prostitution,” and her unrestrainable sexuality is shown as being the core of her nature. These patterns are often applied to bipanqueer woman—our sexual appetites apparently know no bounds. We are inherently promiscuous and incapable of loyal monogamy. Many lesbian women are unwilling to enter relationships with bi women because they think we will inevitably be unfaithful or leave them. For straight men, bi women’s sexuality is still seen as unquenchable except instead of seeing this negatively, some straight men believe we are willing to engage in any sex act at any time with any person—or persons. However, I take joy in my sexuality that is free and unbounded, and I’m delighted that Gomer is the same. She knew what society thought of her—that is inescapable—but she enjoyed her sexuality, was brazen and forthright. She expressed her sexuality freely with an “adulterous look on her face,” and she knows her worth and claims it in olive oil and new wine. For Gomer and myself, it is impossible to contain not just our sexuality but the whole of ourselves. My sexuality has given me the gift of ignoring boundaries.

Another thing that is integral to Gomer’s story and my experience as a bi woman is how we exercise our autonomy. Society wants to enforce its monosexist boxes, but we can choose to live outside hetero- or homo-normative spheres. I have chosen a cis male partner, but that does not mean I have chosen a “straight” partnership. My partnership is queer because I am queer. Likewise, Gomer may have chosen Hosea, but that does not mean she chose to be circumscribed by the limits presented in Hosea. Without the assumption that Gomer is innately promiscuous, the narrative structure that she was constantly leaving her husband and returning to prostitution falls apart—it is not even necessarily supported by the text, as scholars disagree whether or not the opening verse in chapter three should be translated “Go, show love to your wife again” or “Go, befriend a woman.” Gomer chose to live with Hosea, to mother his children, but something that is clear to me as a bipanqueer woman is that Gomer did not choose to destroy herself in the process. She remained independent and autonomous, even in the face of a “yolk on her fair neck.” She defied expectations, as all bipanqueer women do.

Another facet of Gomer’s story that is analogous to my own is that she does, ultimately, choose a role and a “lifestyle” that, on the surface, conforms to her prescribed roles. She became a wife and mother, and according to the writer(s) may have “reformed.” I married a cis man, and hope to become a mother. In the meantime, I am mostly a “stay at home wife.” In an ironic twist of fate, my “lifestyle” more closely resembles the fundamentalist, patriarchal ideal than many of the women who were my peers in fundamentalism and would still consider themselves fundamentalists. A brief glance at the superficial facts of my life reveal a woman who works from home, who performs many of the traditionally feminine domestic duties like cooking and laundry. My partner takes on many of the traditionally masculine ones—managing our finances, mowing the lawn, etc. These “facts,” however, are not because we are obeying a complementarian understanding of marriage, but because I am allergic to grass and obsessed with Food Network, while my partner is genuinely overjoyed by spreadsheets. A deeper look would reveal many aspects of our lives that would horrify anti-feminists.

The text does not offer readers a deeper look into Gomer’s inner life, but if we remove the typical evangelical narrative structure and all the assumptions about her character, I believe we can achieve a more subversive and hopeful telling. Reading from a queer perspective offers the ability to see Gomer as a consistently destabilizing force. Women like Gomer and myself will always remain threats, as our sexual identities will always introduce instability into patriarchal structures. We can refuse yokes, cajoling, or demands and stay true and loyal to ourselves; the men who surround us know this, and should fear their inability to control us. Gomer knows she can provide for herself without Hosea and that she can be content, even happy, without him. I know that I do not need patriarchy, heterosexism, or monosexism to sustain either my Christian identity or my marriage. Even when we arrive at a place or a time in our lives when patriarchy or queerphobia may approve of our choices, we do not make those choices for anyone but ourselves.