An . . . interesting . . . thing happened on Sunday. If you follow me on twitter you probably already saw it, but in case twitter isn’t your thing, I gathered it all up here. You should probably go read it real quick in order for the rest of the post to make sense.

A lot of the responses I got to what happened were along the lines of “WTF” and “wow, you should really get the hell out of there.” To an extent, I don’t really disagree. What happened on Sunday was, in a word, wrong, and it should not have happened. I’m still deeply troubled by it, and me and Handsome are figuring out what we could do– and if we should do it, especially since we’re already approaching the elder board and senior pastor about two other things, which I’ll talk about in other posts.

I’ve reached out to this pastor before about an inappropriate joke he’d made and his response to my e-mail bothered me. I did my best to be gracious– he is incredibly busy, he was responding to my e-mail among a hundred others, and he probably wouldn’t have said what he did if he’d had more time. However, his “I’m sorry that’s what you heard– here, we have a counseling ministry” was off-putting because it implied that you only think what I said was wrong because you have issues. Because of that, I’m hesitant to send him another e-mail that’s nothing more than a critique of his sermon. I don’t want to be the congregant that has nothing encouraging to say, and since I’ve never interacted with him outside of shaking his hand occasionally, I’m not sure how to proceed.

So, the question I have right now– and a question I’ve heard echoed from many of you– is why do I stay here? Why bother? Why keep going? It’s a question I’ve seen all over the place– and usually not directed at me and my situation. It pops up in comment sections all of the time– if your church is doing something like this, why do you stay? Why not just walk away? Sometimes they advocate to drop church entirely, but most of the time they recommend a different denomination.

This is not intended to be disparaging toward anyone– leaving church altogether is, depending on your situation, could be the absolutely best thing for you. Trying another denomination can be spectacular and life-changing. I read a lot of blogs that are actually dedicated to this transition– women who grew up Baptist that are now Catholic, men who grew up evangelical that are now Anglican . . . and it can be a beautiful, refreshing thing. Those blogs have had me running to the ELCA, UMC, PCUSA, and UU websites looking for another option. In those moments, all I can think is surely a denomination that ordains women would be better. Going to a denomination that ordains LGBTQ people? Wow, sign me up.

But there are things holding me back from making that transition right now, and I wanted to explain why. Simply switching denominations sounds so simple, so straightforward; after all, if you don’t like where you are, there’s nothing really keeping you there. But, for me at least (and I think many others), it’s not really that simple.

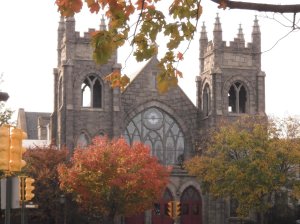

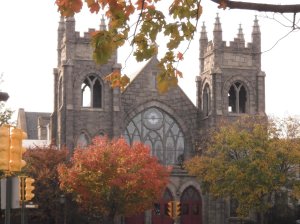

The biggest reason, up front: Handsome has been attending this church for three years now. I’ve been attending for a year. We’re involved in this church, and we are both well-known to the leadership. Handsome has been serving in two separate ministries practically from the moment that he started attending, and now we’re both involved in two others. We facilitate one of the theology classes (it’s a video course, so we just manage discussion and occasionally prepare notes), and we’re both consulted on church organization and structural development (it’s a young church). The leadership that we know trusts us, and I cannot overstate how valuable I find that. The fact that we are as young as we are– I’m 26, Handsome is 25– and we’re respected and our insight and advice is sought? I don’t know how rare that is, but it’s certainly nothing I’ve ever experienced.

And, what if we do go to another church? We’d have to start from scratch. We’d be strangers- nobodys. No one would have any reason to trust us, or listen to us, and what if there was something that was just as problematic in this new church? At least, at this church, I know that the elders and most of the leadership is willing to listen to me.

Second, and there is no possible way I could overstate how incredibly important this is to me: this church is racially diverse. There are black men and women in highly visible leadership positions. Black men serve on the elder board. I look around the auditorium on Sunday morning, and I see black, hispanic, Indian, and Asian people– and not just a light sprinkling. There have been a few mornings where I have been almost completely surrounded by people who aren’t white.

The most interesting thing about this is that I live in an area that is deeply, deeply segregated. The first week I lived here I went shopping for the house (Handsome didn’t have a broom!). The first place I went was Big Lots and Ollie’s and a few other discount stores, looking for floor mats and potholders. The entire morning I was the only white person anywhere. That afternoon I went to Wal-Mart and Ross (which are in a different part of town), and I didn’t see a single non-white person for three hours. In this county, white people and brown people don’t eat in the same restaurants, shop in the same stores, go to the same bars, or attend the same churches. When I look at the websites for the ELCA, UMC, and PCUSA churches that are “nearby” (read: 45 min+ drive), every single last picture is of a white person. All of them. Even the group pictures that seem to be most or all of the congregation. Even the ELCA church, which is in an almost-nearly-black neighborhood, every single last church member is white.

It is amazing to me that this church managed to overcome that monumental barrier in this community. They were deliberate about being diverse– on one occasion when the church was first starting and one of the staff, a black man, was considering leaving, the senior pastor and the elder board begged him to stay, because they knew that if he left, the church was doomed to being just another white church. He stayed, and now I see an Indian family in the lobby every Sunday and a black woman sings and shouts behind me every service I’m there.

by Rachel Hestilow

Third, I live in an extremely conservative county. It is Southern, and it is redneck, and it is Tea Party Republican, and the overwhelming majority of the churches are outright fundamentalist– or at the very least “fundiegelical.” Even in the churches that belong to progressive denominations, the people who attend the church are going to be overwhelmingly conservative, and that is going to affect the entire church culture.

In the church I attend, though, even though I’m a heretic by most Protestant standards (between the universalism-ish and the Pelagianism . . .), and even though I’m a pro-choice Democrat, I can talk about that with the people I go to church with, in my small group and in my theology program, and not face any condemnation or judgment for that. And it’s because, right along with racial diversity, the motto “in essentials unity, in non-essentials liberty, in all things charity” is taken pretty doggone seriously. There are Quiverful families in this church, and there are single working mothers, and there are politics of all stripes, and we all go to church together– and we’re led by people who have no patience for self-righteousness and judgment. I’m sure I could probably find another church that has this, but I know I have that here, and I’m not willing to risk it yet.

~~~~~~~~~~

I know this has been a longer post than normal, so thank you for your patience. This post, although it’s about my experience, isn’t really about me, either. Everyone has reasons for being where they are– even in church situations that are questionable and troubling. I very much appreciate the insight, the concern, and the life experience here in this community, and I always take your advice seriously. And, this post was really directed at myself, as well. Why do I stay here? Well, I may eventually get to the point where I just can’t do this church anymore– and that day may be coming faster than I’d like.