I first heard about Nate Pyle a while ago, when I read his post “Seeing a Woman” after a colleague posted it on Facebook. I appreciated what he had to say there, and over the last two years he’s become someone with whom I don’t always see eye-to-eye, but I still appreciate. I’ve shared his work a few times, and his voice has proven to be extremely effective at reaching an audience I usually can’t.

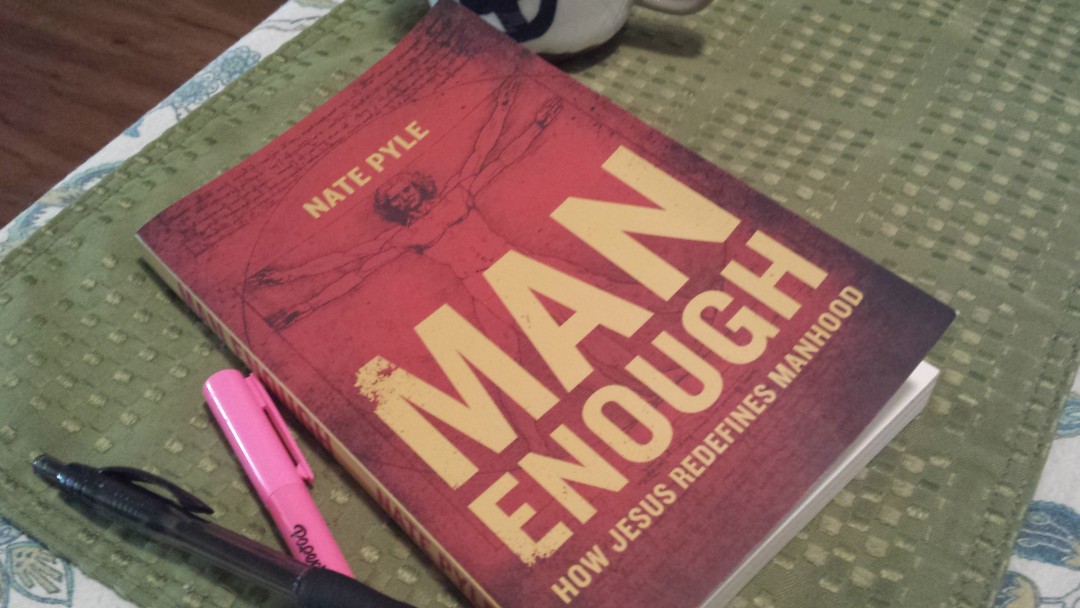

So when Sarah Bessey (another person I don’t always see eye-to-eye with) posted a blurb on her page about Man Enough: How Jesus Redefines Manhood, I was curious, and after looking into it I decided this was a book I needed to review (and thanks to my Patrons, I was able to buy it).

There was only one thing I didn’t like about Man Enough. There is a general feel of “the exceptions prove the rule” approach to gender essentialism. While he acknowledges that some women and some men won’t conform to whatever concept he’s discussing at the time, he is comfortable with saying “all women” and “all men” or things like this:

When I play with my young nieces, we never play this game [breaking things like lego towers]; rather, we play house. The imaginative games are always relational in nature … They are always face-to-face and involve a lot of talking.

While extremely simplistic, these examples highlight a general difference between men and women. Men love to be agents of change in the world. … Even in these differences [some men value strength, others value creativity, etc], there is commonality– changing and influencing the world according to our will. (160)

Personally, I think that the wide acceptance of gender essentialism hurts church and ministry effectiveness. If you believe that there is something(s) inherent to being a man or a woman, that will always be a part of how you view them; in my opinion, that view prevents you from seeing a person, in big or small ways, as a unique individual with their own gifts, priorities, and weaknesses. In this case– “men like to be agents of change”– it made me think, well what the hell does he think women like me are doing? If you ask most of the people who know me, they’d tell you “being an agent of change” is my #1 desire, every other priority pales in comparison, and I don’t think I’m an “exception.” I can think of a lot of men who couldn’t give a rat’s ass about this, while nearly every woman I know does.

A book that’s 194 pages long will, by necessity, have some generalities, but I think Nate needs to step back and evaluate this gender essentialist question some more. Is it that men and women have inherent differences, or that the harsh gender binary in America has given men and women, generally speaking, a similar set of experiences and expectations that are divided along strictly regulated lines? That he doesn’t seem to have wrestled with this is a significant weakness in his argument.

But that’s my only real problem, and even I can admit that a lot of his “I’m not trying to erase gender differences” bits are probably intended to make a conservative evangelical comfortable in a book that shouts about a lot of feminist and social justice issues. I highlighted a lot of things I loved, like these:

The inherent danger of equating some Christlike characteristics with masculinity but not with femininity is that we fail to engage women in discipleship that calls them and sanctifies them into the image of Christ. (49)

The problem with militant portrayals of Jesus is that they can quickly and easily be co-opted to endorse the subjugation of those deemed less than masculine– whether that is expressed through racism, sexism, or homophobia. (66)

Using the gospel to reinforce gender roles and ideals redirects our attention away from its central goal: that men and woman will become like Jesus. (157)

I think the strength of this book is that it addresses a lot of the systemic problems present in modern, and extremely gendered, evangelicalism. Nate explains the history and cultural movements that brought us here, and points out that parts of “Christian culture” may not be Christian at all– and he does it all without using feminist or social justice buzzwords that could be off-putting to the very people who desperately need to read this.

One of my favorite themes that he weaves through the second half of the book is that modern “masculinity” is anti-vulnerability in pretty much every conceivable way, but that choosing to be vulnerable is how we develop intimacy in our relationships; it’s how we can make the truest, deepest connections. I encountered that lesson– again– last week when my pro-choice article went up on xoJane. I was taking a beating in the comment section until I was vulnerable. I would have had every right to be defensive, but I chose to be vulnerable with people who were attacking me, to be honest about the grief and remorse I feel. That decision changed some people’s minds and affected others who might have been on the fence about me. I was able to make connections with people– however fleeting they might have been.

Vulnerability is hard. Most of the time it sucks because it requires a level of introspection and self-awareness that can be painful. Vulnerability frequently means risking pain, because truly exposing ourselves is almost always a risk. Nate blends in his own story of coming to terms with vulnerability, honesty, and authenticity in his life, and how embracing those principles enabled him to love others the way he feels called by Christ to do– and it was interesting seeing him trace his steps in his journey toward understanding who he actually is, and not living up to what culture– Christian or secular– says he must be.

In short, I very much recommend this book. I think it is successful for its intended audience, and I’ve known a lot of men who could have used the encouragement in this book. I spend a lot of time on this blog going through the books that put Christian women into a cage, but Man Enough reminded me that it’s not just women who are affected by gender roles. I could never have embraced my true identity in complementarianism, but neither can a lot of men. As long as we’re all being forcefully shoved into a box we don’t fit in, no one is going to be free, or whole.