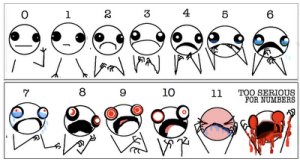

[Hyperbole and a Half‘s “Pain Scale“]

[also, I talk about feminine health concerns. If that squeeks you out… well, uhm . . . awkward]

I have a medical condition known as Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome, complicated by endometriosis. If you know what those two things are, then you know exactly the kind of pain levels I’m talking about. The first time I had a soft hemorrhagic cyst at fourteen, I was completely immobile for two weeks, and the first word the doctors started using was cancer. Turned out it wasn’t cancer– it was PCOS. Every month I deal with excruciating, debilitating pain– I have to take prescription narcotics, and they barely touch it. I can’t hold a full-time job because of it, and I’ve wound up in the hospital twice– once, I got there in an ambulance after I passed out in the middle of class and went into shock.

Which is why, at fourteen, I started taking the Pill. It’s the only possible way of controlling the cysts and preventing them from forming. I still have to deal with the pain of endometriosis, but at least I don’t have to deal with cysts rupturing.

When I first started taking them, the doctor gave me the lowest-dose Pill she could find. It wasn’t enough. We had to gradually up the dosage, and, ladies, if you’ve ever taken the Pill, you’re probably familiar with the wild emotional basketcase you can turn into when you’re on it. Some women don’t have any sort of reaction at all, but for some, it takes us a while to adjust to the higher hormone levels.

I had a terrible time adjusting. At fourteen, I was already dealing with puberty, the pain– throw the Pill in on top of that, and it was just not a very happy situation. I can remember being extremely irritable. Me and my younger sister were already having problems constantly bickering, and that situation deteriorated. I was constantly frustrated, but my emotions were all over the place. I would cry at anything. Things that were only passably funny became wildly hysterical.

I’m not sure how long this went on– probably not much longer than a month — before my mother sat me down at the kitchen table with her Bible. She showed me five passages:

Proverbs 25:28 “He that hath no rule over his own spirit is like a city that is broken down, and without walls.”

Proverbs 16:32 “He that is slow to anger is better than the mighty; and he that ruleth his spirit than he that taketh a city.”

II Peter 1:6 “And to knowledge temperance; and to temperance patience; and to patience godliness.”

Galatians 5:22-23 “But the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, longsuffering, gentleness, goodness, faith, meekness, temperance.”

I Corinthians 9:25 “And every man that striveth for the mastery is temperate in all things.”

There’s a few key phrases here– the first one being rule your spirit, and the second being temperance.

What my mother was highlighting was a valuable lesson– having a modicum of self-control is a necessary component for maturity. What neither me nor my mother was aware of at the time was how these particular verses were going to be used against us for the next six years.

By the time I was fourteen, I’d already endured a great deal of pressure to conform. I was growing up in the fundamentalist South– a place where women are eternally “young ladies” (a term I now refuse to use) and having “lady-like behavior” was the only means any woman had of interacting with people. Unfortunately for me, I was . . . well, rambunctious is one way of putting it. I was also innocently unaware of pretty much anything– how far my skirt was hiking up when I climbed a tree, what my neckline was doing when I bent over or played on the ground . . . My interactions with boys were always incredibly troublesome to the women at my church– because I didn’t really care that they were boys. I played with boys the exact same way I played with girls. I even punched them, slapped them, and threw Kool-aid on their starched white shirts when it was necessary.

I was also loud, and wild, and so very emotional.

Well, at least, I was constantly told I was.

Looking back, there was absolutely nothing out of ordinary with my behavior. I was a teenager. I still have a high amount of energy, my friends can tell you I’m fully capable of talking your ear off, I’m bouncy and enthusiastic, I’m spunky and full of snark. My mother used to describe it as a “thousand watt lightbulb among nightlights.” Throughout my teen years, I can see my mother, almost desperately at times, trying to undo the damage of what I was learning at church.

I spent my teen years focused on playing the piano, reading, or writing. I still have a few of the stories I wrote– the ones I bothered to type, at any rate. And, going back through those stories and through old journals, there’s a common theme.

All of my stories involve a teenage girl who is horribly abused, or has experienced some traumatic event.

All of these girls are silent. One girl had her memory wiped. Another was under a gag order. Another was brainwashed into silence.

All of these girls were what I considered, at the time, the “ideal,” at first. They were painfully quiet. Reserved. Private. All of my heroines experienced some life-altering moment when they were allowed to be who they were. Bright and vivacious, usually.

I wasn’t even aware that I was doing this when I was a teenager. I was completely incapable of identifying of how I was being stifled by being told that “ruling your spirit” was necessary for my survival as a person, or having “Samantha, temperance!” shouted at me across a parking lot. By the time I got to college, these lessons were deeply engrained; I believed that being emotionless was the ideal for Christian women. Compound teachings on “ruling your spirit” and “temperance” with all the rhetoric about women being “meek and quiet” and what you end up with is a mouse.

I’ve never been able to be a mouse– but, oh, I desperately wanted to be.

I remember, during a conversation with a friend, that I talked about being able to turn my emotions on and off– like it was as easy as flipping a switch. I honestly believed it at the time; she thought I was exaggerating, but I felt that it was true. I could just shut down any emotional response, and I perceived any emotional response as being innately bad, even positive ones like happiness.

When I was in my relationship with John*, part of how I justified the abuse– which I had no idea was abuse– was that his domineering control of every single element of my life was allowing me to become who I’d always wanted to be: a mouse. A non-person. Someone who was not able to express emotion, for any reason. Quiet, meek, reserved. Finally, I thought, I had it. And John had gotten me there– being with John had taught me, finally, how to “rule my spirit.” For the first time, I could exercise complete control over my emotions. What I didn’t realize was that I wasn’t controlling anything. John was.

There’s a parallel here: in fundamentalism, and more specifically in Christian patriarchy, women are constantly told to be a very specific kind of woman, to have a specific type of personality. In Christian patriarchy, there’s constant pressure for women to live up to an impossible ideal, and the ideal includes a very narrow way for women to behave, and to be. There’s no room for independence. Women are handed a list of objectives: meek, mild, quiet, gentle, chaste, compliant, passive, dispassionate, detached, tranquil . . . and most of those objectives revolve around being emotionless.